Each year, thousands of people arriving at our border or already in the United States apply for asylum, a form of protection from persecution. People seeking asylum must navigate a difficult and complex process that can involve multiple government agencies. Those granted asylum can apply to live in the United States permanently and gain a path to citizenship. They can also apply for their spouse and children to join them in the United States. This fact sheet provides an overview of the asylum system in the United States, including how asylum is defined, eligibility requirements, and the application process.

What Is Asylum?

Asylum is a protection grantable to foreign nationals already in the United States or arriving at the border who meet the international law definition of a “refugee.” The United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees define a refugee as a person who is unable or unwilling to return to their home country, and cannot obtain protection in that country, due to past persecution or a well-founded fear of being persecuted in the future “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” Congress incorporated this definition into U.S. immigration law in the Refugee Act of 1980. Asylum is technically a “discretionary” status, meaning that some individuals can be denied asylum even if they meet the definition of a refugee. For those individuals, backstop forms of protection known as “withholding of removal” and relief under the Convention Against Torture may be available to protect them from harm.

As a signatory to the 1967 Protocol, and under U.S. immigration law, the United States has legal obligations to provide protection to those who qualify as refugees. The Refugee Act of 1980 established two paths to obtain refugee status—either from abroad, as a resettled refugee, or in or arriving at the border of the United States as a person seeking asylum. This fact sheet does not describe the law or process for gaining refugee status abroad.

In accordance with U.S. law, to apply for asylum, an individual must be physically present in the United States or arrive at a port of entry.

With or without a lawyer, a person seeking asylum must prove to the government that they meet the definition of a refugee. To win asylum, an individual is required to provide evidence demonstrating either that they have suffered persecution in their home country on account of a protected ground in the past, and/or that they have a “well-founded fear” of future persecution in their home country. An individual’s own testimony is usually critical to their asylum determination, and can be supplemented by additional evidence if available.

How Does Asylum Help People Fleeing Persecution?

An asylee—that is, a person granted asylum—is protected from being returned to their home country, is authorized to work in the United States, may apply for a Social Security number, may request permission to travel overseas, and can petition to bring family members to the United States. Asylees may also be eligible for certain government programs, such as Medicaid or Refugee Medical Assistance.

After one year, an asylee may apply for lawful permanent resident status (i.e., a green card). Once the individual becomes a permanent resident, they must wait at least four years to apply for citizenship.

Can a Person Be Barred from Obtaining Asylum?

Yes, certain factors bar people from being granted asylum. For example, with limited exceptions, people who fail to apply for asylum within one year of entering the United States (more about this deadline later) or who have previously been deported and then reentered the United States will be barred from receiving asylum. Similarly, applicants who are found to pose a danger to the United States, who have committed a “particularly serious crime,” or who persecuted others themselves, are barred from asylum.

If a person is barred from receiving asylum, they may be eligible for more limited forms of protection through withholding of removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act or withholding of removal or deferral of removal under the Convention Against Torture. If granted, these forms of protection prohibit the person from being returned to their home country and they receive the right to remain in the United States and work legally. These are more limited protections because they do not provide a path to lawful permanent resident status and the government is still allowed to deport the person to a different country if it is safe to do so and if that country agrees to accept them.

Noncitizens can request asylum before either U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) or an immigration judge in removal proceedings; however, generally, they can only request withholding of removal or protection under the Convention Against Torture before an immigration judge, as is discussed in the next section.

How Do People Request Asylum?

There are two primary ways in which a person may apply for asylum in the United States: affirmatively and defensively. A regulation issued in 2022, referred to as the Asylum Processing Rule, created a third pathway for some individuals arriving from the border which includes elements of both affirmative and defensive asylum processes on an expedited timeline.

- Affirmative Asylum:A person who is not in removal proceedings (or a person who has been designated as an “unaccompanied child,” even if in removal proceedings) may affirmatively apply for asylum through USCIS. A USCIS asylum officer interviews the applicant, and if they find the applicant is eligible for asylum, they may grant asylum as a matter of discretion. If the USCIS asylum officer does not grant the asylum application and the applicant does not have a lawful immigration status, USCIS refers them to the immigration court for removal proceedings, where they may renew the request for asylum through the defensive process and appear before an immigration judge.

- Defensive Asylum: A person who is in removal proceedings (i.e., immigration court) may apply for asylum defensively by filing the application with an immigration judge at the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR). In other words, asylum is applied for as a defense against removal from the U.S. Unlike the criminal court system, EOIR does not provide appointed counsel for individuals in immigration court, even if they are unable to retain an attorney on their own. The defensive asylum process includes people subject to the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), who are required to wait in Mexico during their removal proceedings. Certain non-Mexican citizens who arrive at the southern border (either at a port of entry or after crossing the border between ports of entry) and ask for asylum can be placed in MPP under current Department of Homeland Security (DHS) policy.

- Asylum Processing Rule: Since May 31, 2022, some individuals and families entering the United States have been subjected to a process established under the interim Asylum Processing Rule. They are first placed in expedited removal and, if they express fear of persecution or torture, are given a credible fear interview. As discussed above, before the Asylum Processing Rule, if a person’s fear was found credible, a defensive asylum claim was initiated before an immigration judge. However, instead of referring those who have established a credible fear directly to an immigration judge, people processed under the Asylum Processing Rule are referred to a USCIS asylum officer for a non-adversarial Asylum Merits Interview (AMI) within 21 to 45 days of their credible fear determination. This interview mirrors that of an affirmative asylum claim. A USCIS asylum officer can then either grant or not grant asylum. Additionally, when an asylum officer does not grant asylum, they also assess a person’s eligibility for withholding of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture. If the interviewing officer does not grant asylum, the case is referred to an immigration judge for “streamlined” removal proceedings where defensive asylum, withholding of removal, and Convention Against Torture relief may be considered.

Is There a Deadline for Asylum Applications?

A person generally must apply for asylum within one year of their most recent arrival in the United States. In 2018, a class-action lawsuit challenged the government’s failure to provide asylum seekers adequate notice of the one-year deadline and a uniform procedure for filing timely applications. The federal district court in that case found that DHS is obligated to notify people seeking asylum of this deadline and required that USCIS and EOIR set up a uniform process for submitting asylum applications to facilitate filing before the one-year deadline.

Asylum seekers in the affirmative and defensive processes face many obstacles to meeting the one-year deadline. Some individuals face traumatic repercussions from their time in detention or journeying to the United States and may never know that a deadline exists. Even those who are aware of the deadline encounter systemic barriers, such as lengthy backlogs, which can make it impossible to file their application in a timely manner. In many cases, missing the one-year deadline is the sole reason the government denies an asylum application. Under the Asylum Processing Rule, a person who passes a credible fear interview is considered to have applied for asylum, which means that the one-year filing deadline is automatically satisfied.

What Happens to Asylum Seekers Arriving at the U.S.-Mexico Border?

There have been significant changes as to how people seeking asylum are treated at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years. For nearly two decades, since 2004, DHS has subjected to expedited removal tens of thousands of people per year who were encountered by, or presented themselves to, a U.S. official at a port of entry or near the border. Expedited removal is a fast-track process which authorizes DHS officers to issue removal orders to certain individuals without a hearing before an immigration judge if those individuals lack the proper entry documents or who seek or have sought entry through fraud or misrepresentation.

People subjected to expedited removal who express a fear of returning to their home country are usually given a “fear interview” to ensure that the United States does not violate international and domestic laws by returning them to countries where their life or liberty may be at risk. Importantly, while this is how people should be processed under law, studies have shown that at times U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers do not properly follow this process.

In addition, due to resource limitations, not every person encountered by a CBP officer at the border is placed into expedited removal proceedings. People who are not placed in expedited removal proceedings are generally given a “Notice to Appear” in immigration court, which formally begins their removal proceedings where they will be required to submit an asylum application. Some people issued a Notice to Appear are released directly at the border, instead of being detained. People released at the border who are not given a Notice to Appear may be able to submit an affirmative asylum application with USCIS.

Recent changes have placed additional restrictions on the ability to seek asylum for people presenting themselves at the U.S.-Mexico border. Since May 2023, the government has restricted asylum eligibility for people who cross the border between ports of entry, although they remain eligible for more limited forms of protection like withholding of removal and protections under the Convention Against Torture. On January 20, 2025, the Trump administration issued a proclamation purporting to prohibit most people crossing the southern border from applying for any forms of protection, even withholding of removal. As of the time of this publication, the legality of these restrictions remains undecided.

“Credible” and “Reasonable” Fear Interviews

Fear interviews are part of the expedited removal process. If a person is subjected to expedited removal, an expedited removal order will be issued against them. However, if they express a fear of returning to their home country or request to seek asylum, they will first be screened before being removed to see if they can establish that they have a fear of persecution or torture.

Generally, there are two “levels” of fear interviews, commonly referred to as “credible fear” and “reasonable fear.” A person is said to have a “credible fear” if they can demonstrate a “significant possibility” that they will be able to establish eligibility for asylum, withholding of removal, or protection under the Convention Against Torture. A person establishing a “reasonable fear” of persecution or torture must demonstrate a higher likelihood that they would be eligible for relief from removal.

The fear screening process has been periodically altered by new rules issued by various presidential administrations. Those rules are also often the subject of litigation, making the exact process an individual is subjected to (including the standard of proof needed to establish a “credible” fear) subject to regular change. Additionally, many of the rules are applied only to a subset of people, often seemingly at random, due to changing logistical, diplomatic, or humanitarian factors. Therefore, the credible and reasonable fear interview process may be applied differently to different people depending on when they arrived at the border, where they arrived, what country they arrived from, whether they entered at a port of entry or between ports of entry, and other considerations.

At the credible or reasonable fear interview, if an individual is found by the asylum officer to have met the standard applied to them, they are then referred to proceedings where they can apply for asylum or other similar protections. Usually, this is done via a referral to an immigration court, where a person is put in removal proceedings initiated with a Notice to Appear. The Asylum Processing Rule creates an alternative avenue where people may have their full asylum cases reviewed by a USCIS asylum officer rather than an immigration judge, on a significantly truncated timeline.

If the asylum officer determines the person did not establish either credible or reasonable fear, their expedited removal order stays in place. Before removal, the person may request review of the fear determination by an immigration judge. If the immigration judge overturns a negative fear finding, they are treated as if they passed their fear interview and are placed in further proceedings through which they can seek protection from removal, including asylum. If the immigration judge upholds the negative finding by the asylum officer, the person will be removed from the United States.

- In Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 USCIS found 70,549 people to have credible fear. However, during the last four months of FY 2024, these numbers decreased due to a presidential proclamation declaring “emergency border circumstances,” which limited access to asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. The proclamation’s associated regulations make most people who cross the border outside of a port of entry (i.e., an official border crossing) or without advance permission ineligible for asylum. In addition, the regulations require people seeking protection to affirmatively articulate their fear of persecution or intention to apply for protection to CBP officers rather than having CBP officers initiate such inquiries, and heighten the burden of proof for people seeking withholding of removal and protections under the Convention Against Torture during the fear screening process.

- Credible fear interviews have skyrocketed since the expedited removal process was implemented—in FY 1998, USCIS conducted 2,726 interviews. Credible fear decisions reached an all-time high in FY 2024 at 169,450.

- In FY 2024, USCIS found 4,627 people to have reasonable fear.

How Long Does the Asylum Process Take?

Overall, the asylum process can take years to conclude. In some cases, a person may file their application or pass a credible or reasonable fear screening and receive a hearing or asylum interview date years in the future. Backlogs, both before the immigration courts and at USCIS asylum offices, have grown dramatically in the past few years.

- As of December 31, 2024, there were 1,446,908 affirmative asylum applications pending with USCIS.

- The backlog in U.S. immigration courts continues to reach all-time highs, with over 3.7 million open removal cases as of January 31, 2025. At the end of FY 2024, 1,478,623 defensive asylum applications were pending in immigration courts.

- Individuals with an immigration court case who were ultimately granted relief such as asylum in FY 2024 waited more than 1,283 days on average for that outcome. The Omaha Immigration Court in Nebraska had the longest wait times, averaging 2,119 days until relief was granted.

People seeking asylum, and any family members waiting to join them, are left in limbo while their cases are pending. The backlogs and delays can cause prolonged separation of refugee families, leave family members abroad in dangerous situations, and make it more difficult to retain pro bono counsel who are able to commit to legal services for the duration of a case.

Although people who have applied for asylum may obtain work authorization after their case has been pending for at least 180 days (or longer in some circumstances), the uncertainty of their future impedes employment, education, and trauma recovery opportunities.

What Happens to People Seeking Asylum While Their Application Is Pending?

People seeking asylum include some of the most vulnerable members of society—children, single mothers, survivors of domestic violence or torture, and other individuals who have suffered persecution and trauma. While U.S. law provides arriving asylum seekers the right to remain in the United States while their claim for protection is pending, the government has argued that it has the right to detain such individuals, rather than release them into the community. Some courts have rejected this interpretation and held that asylum seekers meeting certain criteria have a right to a bond hearing, which could result in release from detention. Advocates have also challenged the practice of detaining asylum applicants without providing a meaningful opportunity to seek parole, another mechanism that could result in release from detention, including class-action suits that document the prolonged detention—sometimes lasting years—of individuals found to have a credible fear who are awaiting adjudication of their claim for asylum.

Detention exacerbates the challenges asylum seekers already face and can negatively impact a person’s asylum application. Studies have found that detained individuals in removal proceedings are nearly five times less likely to secure legal counsel than those not in detention. This disparity can significantly affect an individual’s case, as those with representation are more likely to apply for protection in the first place and successfully obtain the relief sought.

How Many People Are Granted Asylum?

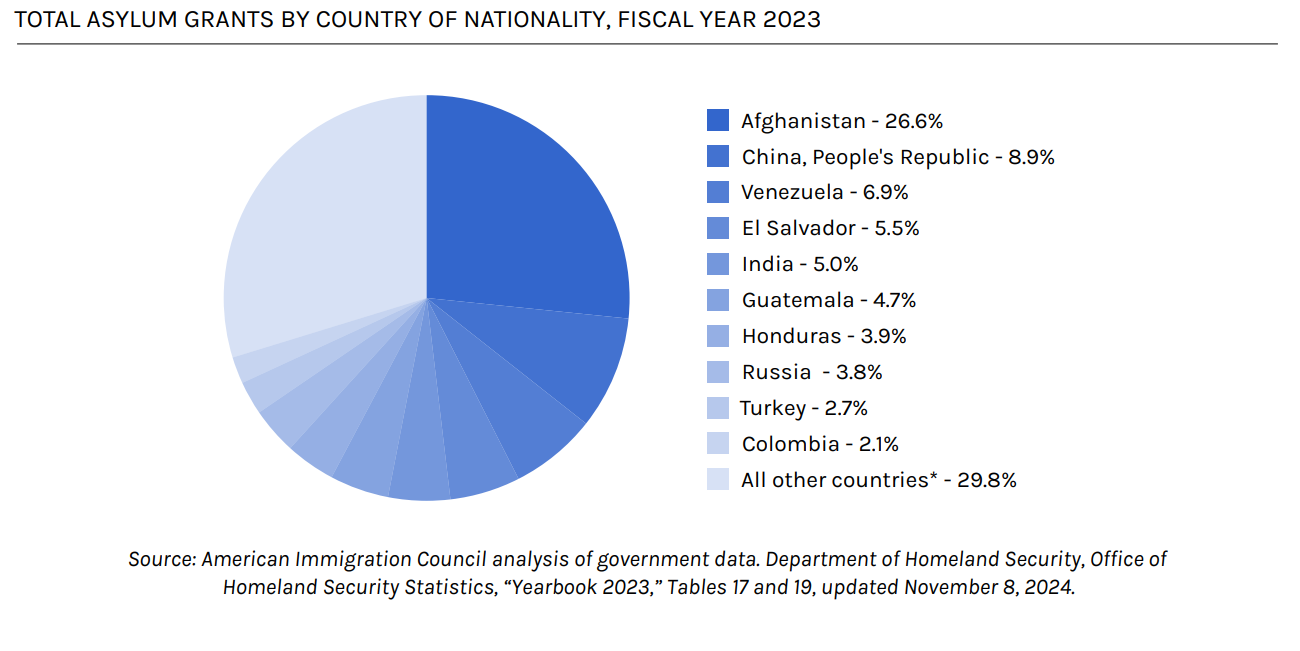

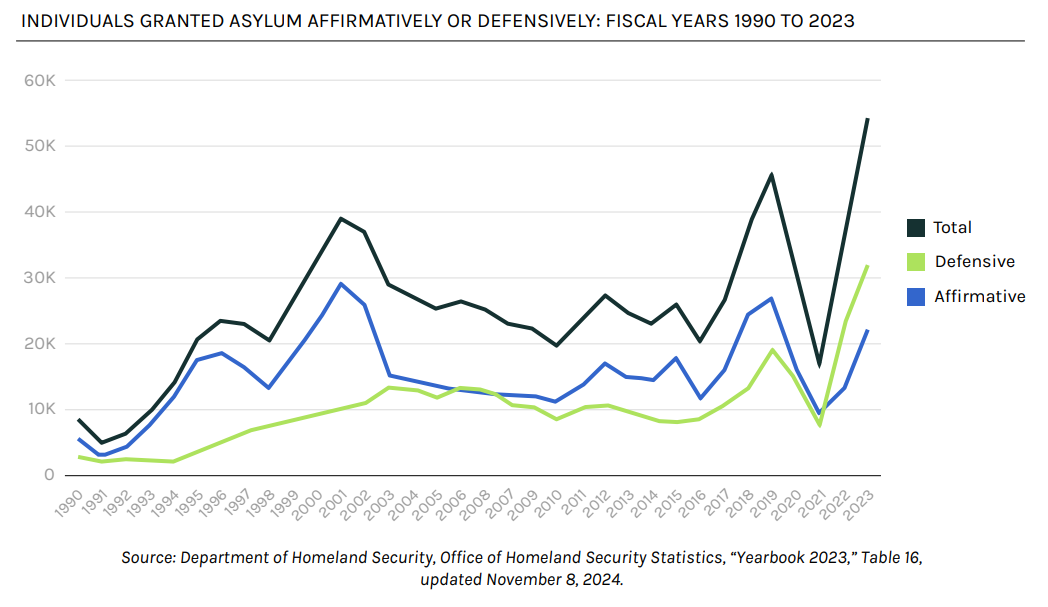

In FY 2023, 54,350 individuals were granted asylum (excluding derivatives, i.e. family members such as minor children who received status as a result of a primary application). These numbers represented a significant increase from FY 2022, which saw 35,720 approved asylum applications. This trend followed a significant decrease in asylum case processing as the asylum system nearly shut down because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In FY 2023, nationals of Afghanistan made up nearly two thirds of the 22,300 affirmative asylum grants, while China, Venezuela, El Salvador, and India made up more than one third of the 32,050 defensive asylum grants. More than 100 nationalities were represented among all individuals granted asylum in FY 2023.