Among many longstanding problems plaguing the U.S. immigration system is the shortage of immigration judges. Over the past decade, Congress has increased immigration enforcement funding exponentially, yet has not provided the immigration courts commensurate funding to handle the hundreds of thousands of new removal cases they receive each year. The resulting backlog has led to average hearing delays of over a year and a half, with serious adverse consequences. Backlogs and delays benefit neither immigrants nor the government—keeping those with valid claims in limbo and often in detention, delaying removal of those without valid claims, and calling into question the integrity of the immigration justice system.

Dramatic Immigration Enforcement Spending Increases, Without Commensurate Court Resource Increases, Have Placed Extraordinary Burdens on the Courts

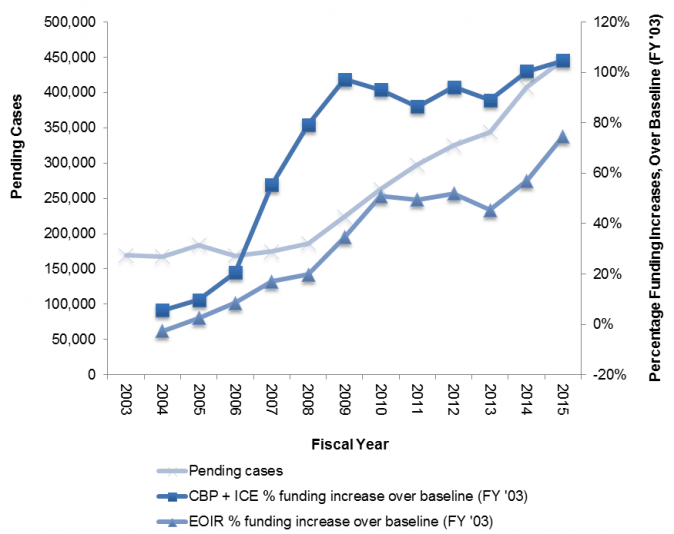

Over the last decade, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) immigration enforcement resources have increased dramatically (Figure 1):

- Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) combined spending increased 105 percent from Fiscal Year (FY) 2003 to FY 2015, from $9.1 billion to approximately $18.7 billion.

- Moreover, the federal government increasingly leveraged state law-enforcement resources for immigration enforcement through programs like Secure Communities and 287(g).

In contrast, as increased enforcement has contributed to immigration court backlogs, court funding has not kept pace (Figure 1):

- Immigration court backlogs increased 163% from FY 2003 to April 2015.

- Immigration court spending increased more modestly—74 percent from FY 2003 to FY 2015, from $199 million to $347.2 million.

- Congress increased funding by $35 million in FY 2015.

- The Administration has requested an additional $64 million for immigration courts in FY 2016.

- Bipartisan calls are emerging for further increases. Immigration Judge Dana Leigh Marks, President of the National Association of Immigration Judges, argues that it is necessary to double or even triple the size of the immigration courts.

Figure 1: CBP & ICE Enforcement Funding vs. EOIR Court Funding, Case Backlog

Source: See endnotes 2, 6, 7 and 8.

High Caseloads, Low Staffing Shape the Courts’ Current Condition

Immigration judges are employees of the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), an agency within the Department of Justice (DOJ).

- Attrition, budget cuts, and burn-out have led to a reduction in judges from 270 in April 2011 to 233 today, with only about 212 judges serving full-time, in 58 immigration courts nationwide. At least 100 judges are eligible to retire in 2015.

- Each immigration judge was handling over 1,400 “matters”/year on average at the end of FY 2014—far more than federal judges (566 cases/year in 2011) or Social Security administrative law judges (544 hearings/year in 2007). Some judges reportedly have over 3,000 cases on their docket.

- In FY 2014, immigration judges received 306,045 matters overall—225,896 removal cases (73.8 percent of all matters), 60,446 bond hearing requests (19.8 percent), and 19,703 motions (6.4 percent).

Growing Court Backlogs Lead to Long Delays

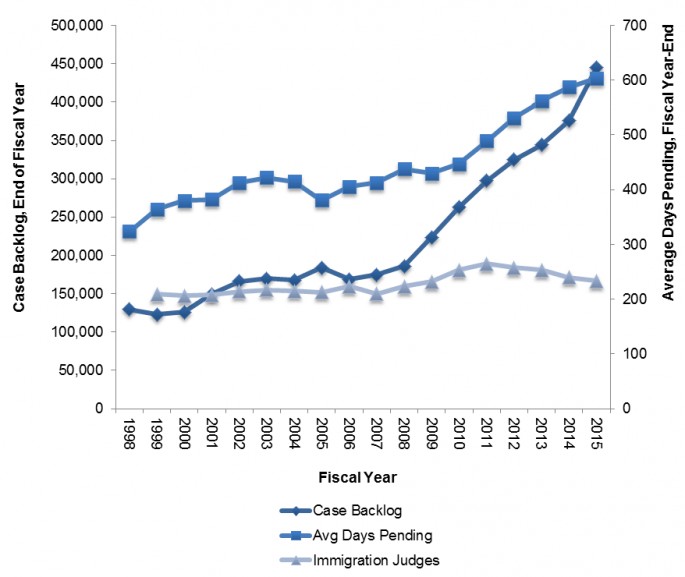

There have been rising immigration court backlogs and case delays since at least 1998 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rising Immigration Court Backlogs & Rising Case Delays While Judges Remain Flat

Source: TRAC, Immigration Court Backlog Tool (FY 2015 data through April 30, 2015); Bipartisan Policy Center, May 20, 2015; Los Angeles Times, May 16, 2015.

- More cases are filed than can be completed. For instance, in FY 2014, courts received 23 percent more matters than they completed (306,045 versus 248,078).

- Accordingly, court backlogs have more than doubled since 2006, reaching 445,607 cases in April 2015—an all-time high, and nearly 30 percent higher than the beginning of FY 2014.

- The average removal case as of April 2015 has been pending for 604 days—nearly a year and eight months.

- Backlogs in large cities are even worse—over two years in Los Angeles (768 days), Chicago (782 days), Denver (819 days), and Phoenix (806 days). Backlogs in Houston (636 days) and New York (605 days) are above-average as well.

“Rocket Dockets” for Children and Families Have Increased Backlogs Across the System

- On July 9, 2014, DOJ issued new guidelines prioritizing the cases of recently-arriving unaccompanied children and families above other cases in the immigration courts. The American Immigration Council and others have criticized these “rocket dockets” for the most vulnerable, and criticized the quick adjudication of cases against unaccompanied children who may have lacked adequate notice of their proceedings or may not have understood the process.

- In any event, these “rocket dockets” neither caused, nor have solved, court backlog problems:

- Backlogs long predate recent Central American arrivals of children and families, as shown above.

- Only 15.7 percent of the current backlog consists of unaccompanied children’s cases.

- Meanwhile, backlogs have increased for everyone else—including many with humanitarian claims, including individuals who cannot obtain work authorization while their immigration court case is pending.

- In fact, since October 1, 2014, backlogs have increased 9.2 percent.

- Indeed, EOIR has essentially taken many “non-priority” cases off the calendar—giving them a “parking date” for a hearing in four years (Nov. 29, 2019), but with the understanding that the court date may move again.

Extreme Immigration Court Backlogs and Delays Benefit No One

Long delays keep applicants with meritorious claims in limbo, restricting their integration into society.

- Immigration Judge Marks pointed out that “with long delays, people whose cases will eventually be granted relief suffer.” For those without valid claims, backlogs simply delay their departure.

- Long delays cause family separation. Applicants also are often unable to work and contribute financially, due to lack of work authorization.

- Many immigrants remain detained during their hearings, including families and children fleeing persecution, with serious negative health impacts. Some detainees with valid claims to stay simply give up.

Pressure on judges to accelerate hearings undermines the overall integrity of the system:

- Overburdened judges are more likely to make wrong decisions when making “split-second decisions regarding complex legal issues.”

- Some immigration judges have reported seven minutes on average to decide a case, if they decided each case schedule for a hearing before them that day.

- Accelerated proceedings put at risk children, whose cases require particular sensitivity, and asylum seekers, for whom “hasty decisions [in cases] could result in loss of lives.”

- Moreover, “haste makes waste,” leading to more appeals and higher fiscal costs overall, as Marks noted.

Conclusion

Problems plaguing the immigration courts will not be addressed by funding alone. Numerous other reforms are necessary to create a more efficient and fair judicial process—most significantly, a meaningful right to counsel. In the short term, however, addressing the basic lack of resources for immigration courts is a necessary step forward. Additional immigration judges would help ensure that all noncitizens have a meaningful and timely day in court, and would help restore the integrity of the system.