The United States has long been a global leader in the resettlement of refugees—and the need for such leadership remains enormous. The number of refugees around the world who are fleeing violence or persecution in their home countries in search of safety abroad has grown dramatically over the past decade.

Until recently, the United States offered refuge each year to more people than all other nations combined, and resettlement received bipartisan support. But the first Trump administration drastically reduced the number of refugees that could enter the United States: the United States resettled only 118,202 refugees between 2017-2020—the fewest in any four-year period since the creation of the U.S. refugee program and the first time in modern history that the United States settled fewer refugees than the rest of the world. Resettlement rebounded during the Biden administration, peaking at 100,034 refugees in 2024 alone. The second Trump administration, though, is attempting to suspend all refugee resettlement indefinitely, except potentially for white South Africans.

Forcible Displacement Is on the Rise Globally

People compelled by force to leave their homes often face two options. They can flee to another locale within their home country, in which case they are known as “internally displaced persons (IDPs).” Or they can flee to another country, becoming “refugees” once they cross an international border and “asylum seekers” once they apply for formal recognition of their need for protection in a third country. A very small subset of refugees—one half of one percent—receive an opportunity for resettlement in a third country and are generally called “refugees seeking resettlement.”

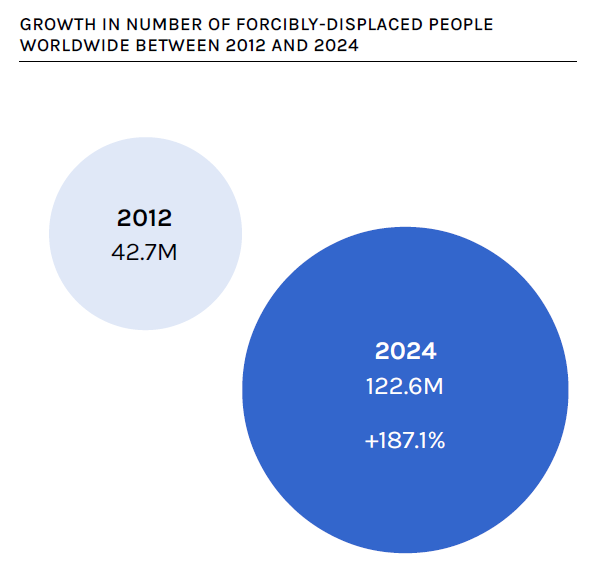

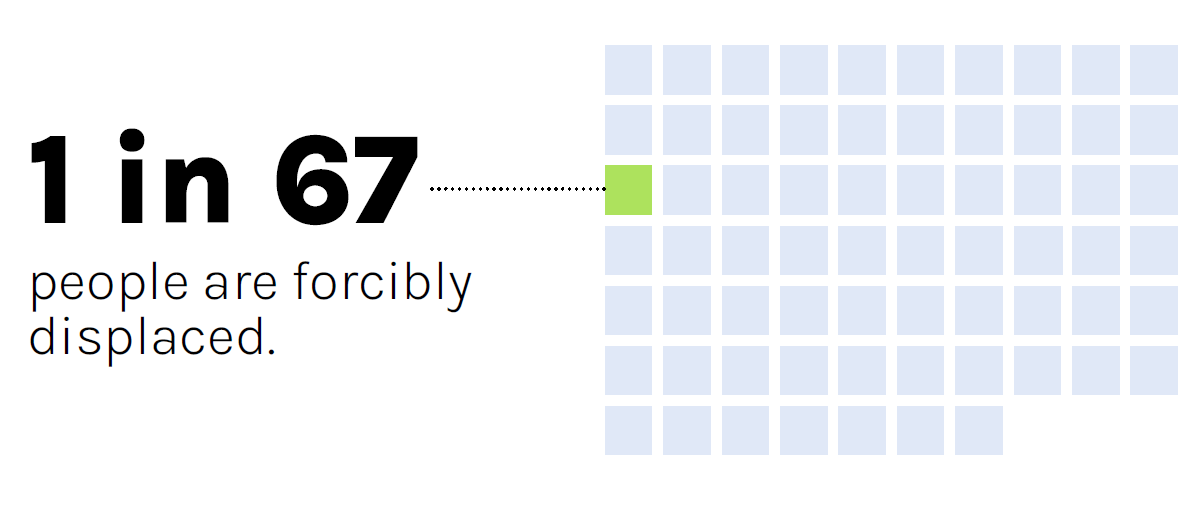

The number of forcibly displaced people around the world has skyrocketed over the past decade, growing from 42.7 million at the end of 2012 to 122.6 million as of June 2024. Presently, approximately 1 in 67 people are forcibly displaced. Much of this displacement has been fueled by new or worsening conflicts around the world, particularly in Afghanistan, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Venezuela, and Yemen.

Refugee Flows Are Increasing Worldwide

Given the rising numbers of forcibly displaced people in general, it is not surprising that the numbers of refugees are also increasing. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there were 46 million refugees worldwide in June 2024—nearly double the number a decade earlier. Children under the age of 18 represent more than 40 percent of the refugee population. The top-five origin countries for refugees under UNHCR’s mandate in 2023 were Afghanistan (6.4 million), Syria (6.4 million), Venezuela (6.1 million), Ukraine (6 million), and Sudan (1.5 million).

The Definition of a “Refugee”

Under U.S. law, a “refugee” is a person who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country because of “persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution” due to race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. This definition arises from the United Nations 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocols relating to the Status of Refugees, to which the United States became a party in 1968. Following the Vietnam War and the U.S. experience resettling Southeast Asian refugees, Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, which incorporated the Convention’s definition into U.S. law and provides the legal basis for today’s U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP).

Additional definitions for “refugee” also exist in international law that differ from U.S. law and the U.N. Convention. The Cartagena Declaration on Refugees—signed by Mexico, most Central American countries, and many countries in the Caribbean and South America—not only adopts the Convention’s refugee definition but expands refugee status to “persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.” Likewise, African Union’s Convention Governing Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa recognizes the Convention’s refugee definition and broadens it to include “every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part of whole of his country or origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.”

Considerable confusion arises about who is a refugee from the different definitions for the term in U.S. law, the U.N. Convention, and regional treaties, as well as the colloquial use of the term to refer to those fleeing terrible conditions in their home countries. Each use of the word encompasses different subsets of the entire population of forcibly displaced individuals. For instance, according to the United Nations, there were 5.8 million displaced abroad in 2023, predominately from Venezuela, who did not qualify as either refugees or asylum seekers under its definition because they fled their homes to escape socioeconomic conditions such as violent crime and poverty rather than persecution. But many of these Venezuelans reside in Brazil, which offers refugee status based on such violence and other human rights violations under the Cartagena Declaration. Thus, who is and is not a refugee often depends on who is speaking and their understanding of the term.

How U.S. Refugee Admissions Numbers Are Determined

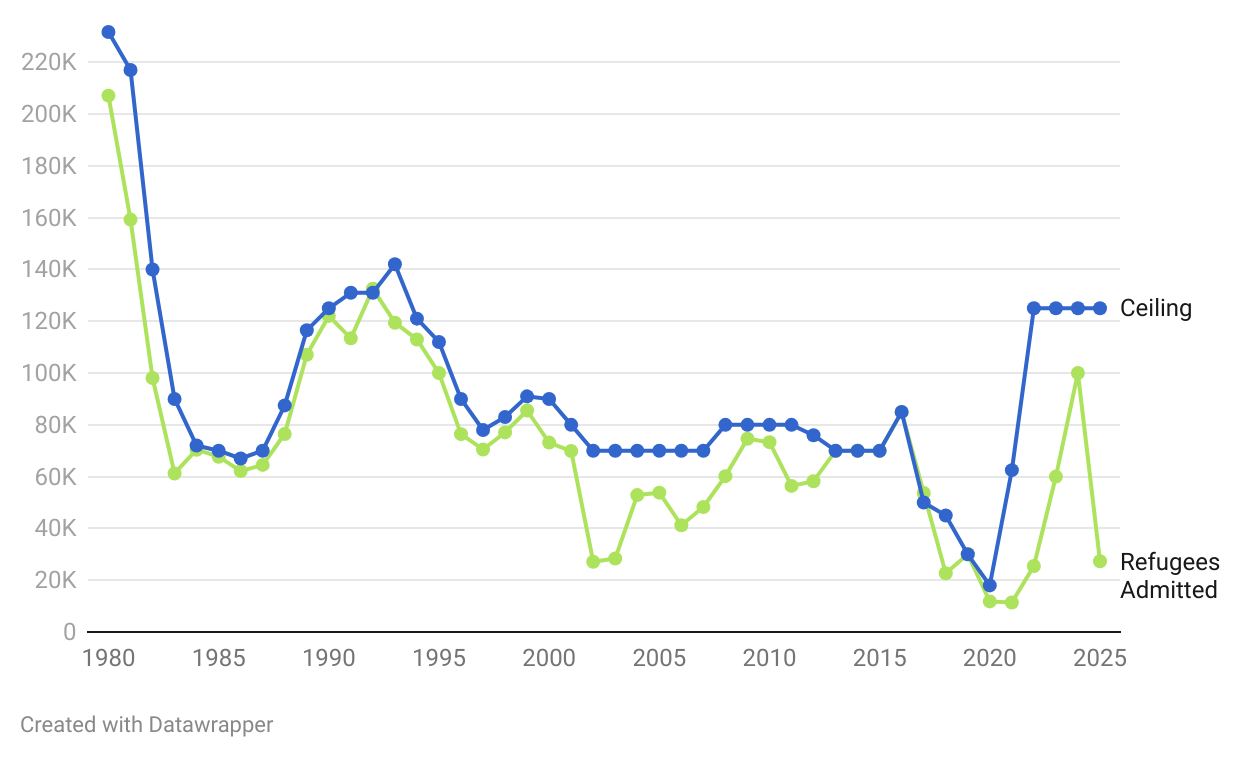

The President, in consultation with Congress, determines the numerical ceiling for refugee admissions each year. The State Department and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) are the primary agencies that assess the eligibility of different refugee populations for admission, as well as the capacity of U.S. government officials to process them. The ceiling for FY 2025 is 125,000—which while more than double the ceilings in FY2017-2020, is nearly one hundred thousand less than the ceilings of the early 1980s.

The annual Presidential refugee determination also provides sub-ceilings for refugee admissions from different regions. Of the 100,034 refugees resettled in the United States during FY 2024, the largest share was from Africa, followed by the Near East/South Asia, Latin America/Caribbean, Europe/Central Asia, and East Asia. Specifically,

- 34,017 (or 34.0 percent) came from Africa—compared to 4,160 in FY 2020 (the last year of the first Trump administration).

- 29,939 (or 29.9 percent) came from the Near East/South Asia, a region that includes Iraq, Iran, India, Syria, and Egypt—compared to 1,999 in FY 2020.

- 25,358 (or 25.3 percent) came from Latin America/Caribbean—compared to 948 in FY 2020.

- 7,540 (or 7.5 percent) came from East Asia—a region that includes China, Vietnam, and Indonesia—compared to 2,129 in FY 2020.

- 3,180 (or 3.2 percent) came from Europe/Central Asia—compared to 2,578 in FY 2020.

U.S. Refugee Admissions and Refugee Resettlement Annual Ceilings (FY 1980-2025)

The Basics of the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Process

There are four principal categories through which individuals can access USRAP:

- Priority One: Individuals with compelling protection needs or those for whom no other durable solution exists. These individuals are referred to the United States by UNHCR, a U.S. embassy, or a non-governmental organization (NGO).

- Priority Two: Groups of “special concern” to the United States, as designated by law or the Department of State in consultation with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), UNHCR, and designated NGOs. Currently, these groups include religious minorities from the former Soviet Union and Iran; Afghans, Iraqis, and Syrians with certain ties to the United States; children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras; Congolese in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Burundi who sought asylum before a given year; and ethnic minorities from Myanmar in Malayasia and Bangladesh.

- Priority Three: The relatives (parents, spouses, or unmarried children under 21) of refugees who are already settled in the United States.

- Priority Four: Refugees whom an approved group of five or more U.S. citizens has agreed to sponsor upon arrival.

With few exceptions, refugees cannot apply for USRAP access directly even if they fall within one or more of the above categories. Rather, they obtain access via a referral sent by a third party: UNHCR refers refugees under its mandate who have certain resettlement needs or satisfy the criteria for certain State Department-designated Priority 2 groups (e.g., Congolese in the Great Lakes); family members in the United States file Affidavits of Relationships (AOR) on behalf of their children in El Salvadorian, Guatemalan, or Honduran or their parents, spouses, or unmarried children living as refugees abroad; U.S. government agencies, nonprofits, and media organization refer Afghans with certain affiliations to them; and approved groups of U.S. citizens file applications on behalf of refugees whom they have agreed to sponsor.

Resettlement Support Centers (RSCs) process the referrals, AORs, and other applications that the State Department receives. RSCs create a case file for each prospective refugee under consideration and request background security checks from U.S. national security agencies including the National Counterterrorism Center, FBI, and the Department of Defense. Officers from USCIS conduct interviews to confirm that the individual qualifies for resettlement under a designated refugee processing priority, meets the U.S. definition for being a refugee, is not firmly resettled in a third country, and is otherwise admissible to the United States under U.S. law.

Applications for refugee resettlement can be denied for a variety of reasons including criminal histories, past immigration violations, alleged connections to terrorist groups, or communicable diseases. An applicant may appeal the decision but only based on a significant error by the USCIS officer or if there is new, previously unavailable information.

Individuals who pass the security and medical checks and receive formal approval from USCIS are eligible for resettlement. RSCs send biographical information on the refugees selected for resettlement to ten domestic resettlement agencies and organize travel to the United States in coordination with the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Before departing, refugees attend cultural orientation classes and sign a promissory note to repay the United States for their travel cost.

The domestic resettlement agencies, many of them faith-based organizations such as Church World Service and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, handle resettlement logistics and consult with local authorities to determine where refugees will live. Refugees resettled in the United States do not need to have a sponsor. If a refugee approved for admission has a relative living in the United States, efforts are made to place the refugee near his or her relative.

The State Department’s Reception and Placement Program provides funds to cover refugees’ rent, furnishings, food, and clothing for an initial 90-day period. The Office of Refugee Resettlement in the Department of Health and Human Services provides longer-term cash and medical assistance, along with other social services such as language classes and employment training to support the integration of refugees into local communities. One year after resettlement, refugees may apply for Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) status. If they adjust to LPR status, they may petition for naturalization five years later.

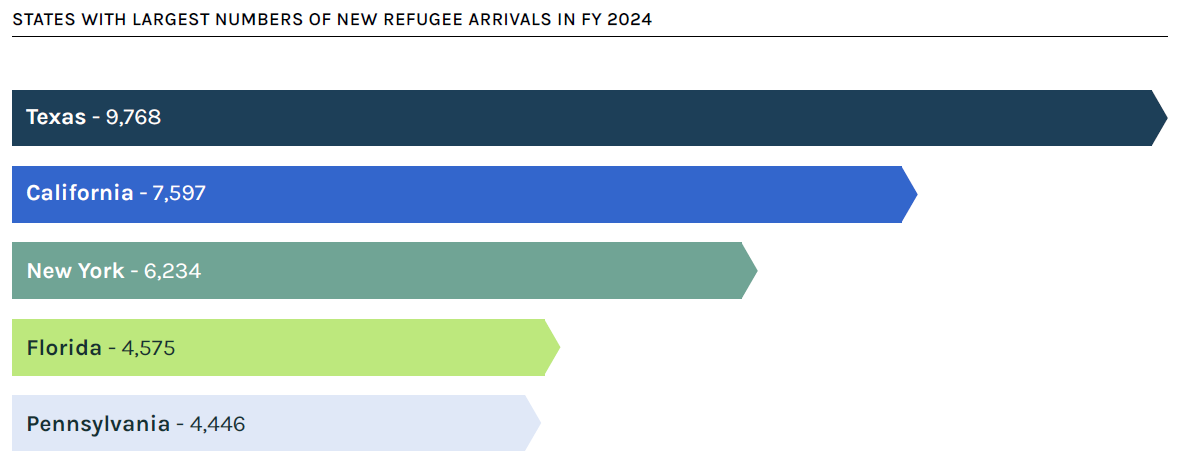

In FY 2024, the largest number of new refugee arrivals settled in Texas (9,768), followed by California (7,597), New York (6,234), Florida (4,575), and Pennsylvania (4,446).

Refugee Resettlement Process Timeline and Uncertain Future

The process of refugee resettlement in the United States is time consuming and increasingly uncertain. Prior to the first Trump administration, resettlement consistently took an average of 18 to 24 months. The first Trump administration lengthened the process by suspending resettlement altogether several times, cutting staff, and imposing new, so-called extreme vetting requirements. While it is still early, the second Trump administration seems intent on ending refugee resettlement all together. It has not only suspended all admissions but has also furloughed staff at RSCs and terminated contracts with domestic resettlement agencies. Litigation challenging the second Trump administration’s actions is ongoing.