- Special Report

No Action Taken: Lack of CBP Accountability in Responding to Complaints of Abuse

Published

Summary

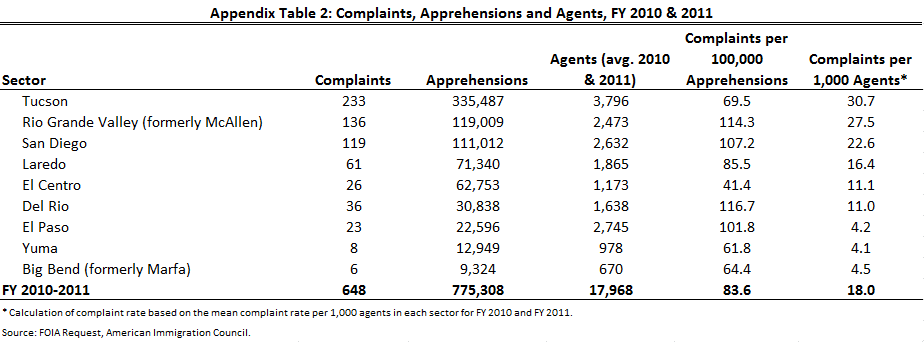

Data obtained by the American Immigration Council shine a light on the lack of accountability and transparency which afflicts the U.S. Border Patrol and its parent agency, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The data, which the Immigration Council acquired through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, covers 809 complaints of alleged abuse lodged against Border Patrol agents between January 2009 and January 2012. These cases run the gamut of physical, sexual, and verbal abuse. Although it is not possible to determine which cases had merit and which did not, it is astonishing that, among those cases in which a formal decision was issued, 97 percent resulted in “No Action Taken.” On average, CBP took 122 days to arrive at a decision when one was made. Moreover, among all complaints, 40 percent were still “pending investigation” when the complaint data were provided to the Immigration Council.

The data indicate that “physical abuse” was the most prevalent reason for a complaint, occurring in 40 percent of all cases, followed by “excessive use of force” (38 percent). Not surprisingly, more complaints were filed in sectors with higher levels of unauthorized immigration. During the time period studied, more than one in three complaints filed against Border Patrol agents were directed at agents in the Tucson Sector. After accounting for the different numbers of Border Patrol agents in each sector, the complaint rate remained the highest in the Tucson Sector, with the Rio Grande Valley Sector a close second. Complaint rates as measured in terms of numbers of apprehensions were highest in Del Rio, Rio Grande Valley, and San Diego. Taken as a whole, the data indicate the need for a stronger system of incentives (both positive and negative) for Border Patrol agents to abide by the law, respect legal rights, and refrain from abusive conduct. In order to do that, complaints should be processed more quickly and should be carefully reviewed. Furthermore, the seriousness of the complaints demands an external review.

A Longstanding Pattern of Abuse and Inaction

For years it has been reported that U.S. Border Patrol agents routinely ignore the constitutional and other legal rights of both immigrants and U.S. citizens. More precisely, agents of the Border Patrol are known for regularly overstepping the boundaries of their authority by using excessive force, engaging in unlawful searches and seizures, making racially motivated arrests, detaining people under inhumane conditions, and removing people from the United States through the use of coercion and misinformation. A 2013 report, for instance, shows that physical and verbal mistreatment of migrants while in U.S. custody is not a random occurrence, but rather a systemic problem. And while this issue currently may be getting more public attention, the use of force by Border Patrol agents against the immigrants they apprehend is hardly a new phenomenon.

The abuse of migrants while in U.S. custody arises from a lack of transparency and accountability not only within the Border Patrol itself, but within its parent agency: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). While officials in any institution may engage in unlawful conduct, such behavior can be minimized or kept in check if there are clear rules, norms, and sanctions that hold those officials accountable. In other words, individuals respond to incentives, and the existence of widespread abuse of authority within the Border Patrol reveals a weakness in the structure of incentives that should guide the behavior of Border Patrol agents.

In addition to the structure of incentives, some of the abuses registered may also be related to the way in which CBP has been hiring and training new staff. Since the adoption of the “prevention through deterrence” strategy in the early 1990s, which resulted in a surge of resources and personnel along the southwest border, the number of Border Patrol agents has been increasing steadily. Although a report from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) states unequivocally that the staffing surge impacted neither the amount nor the type of training that CBP personnel receive, many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) suggest otherwise. Moreover, a report from the Congressional Research Service says that the rapid expansion in the number of agents has led to a decline in the level of experience of agents in the field. The report also casts doubt on whether the growth in manpower in recent years has been matched with appropriate training and other procedures to make sure that new agents are adequately integrated into the force. All in all, the ramping up of hires, possibly coupled with reduced or inadequate training and experience, may have resulted in the presence of agents who do not have the skills to deal appropriately with people in stressful situations.

Based on data provided to the American Immigration Council in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, this report sheds light on one of the few avenues available to people to directly report mistreatment by Border Patrol agents—namely, the filing of complaints. Individuals who have been subject to alleged misconduct by Border Patrol agents or other CBP officials may submit complaints to DHS through various channels. Complaints regarding criminal and non-criminal misconduct by CBP employees or contractors can be submitted directly to DHS OIG, to the Joint Intake Center (JIC), to CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs (OIA), and/or to DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL). OIG screens the complaints of CBP misconduct it receives directly as well as those submitted through other channels. If OIG declines to investigate a complaint, it will either be returned to the originating office or, with respect to complaints submitted directly to OIG, sent to CRCL and/or to the JIC for referral to OIA. It is from the subset of complaints passed along to CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs by DHS OIG that the data in this report is derived. In addition, complaints may also be filed with local CBP offices. In other words, there is no unified system through which the agency receives all complaints from individuals who allege that they have been improperly treated by CBP.

In principle, the receipt and investigation of complaints sounds like an invaluable opportunity for the agency to learn from any systematic problems that may affect the behavior of its personnel, and—where necessary—improve their performance through enhanced training and/or policy directives. However, the findings of this report show that the complaint system is a rather ornamental component of CBP that carries no real weight in how the agency functions.

The data underlying this analysis consists of a set of complaints filed against CBP during the period January 2009 through January 2012. CBP produced this data set in response to FOIA litigation by the Immigration Council which sought records relating to complaints filed by an individual (or by an organization on behalf of an individual) which alleged either general misconduct of any type by a Border Patrol agent or, more particularly, that an agent used coercive tactics—such as threats of violence, sexual assault, or retaliation—to persuade an individual to accept voluntary return to his or her country of origin. The Council’s request for records was limited to incidents occurring within 100 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border.

In response, CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs produced a document listing 809 complaints against Border Patrol personnel. Even though this is valuable information for analytical purposes, it is safe to assume that only a very small fraction of individuals who are victims of abuse would actually file a complaint. It is unlikely that those who have been deported or those with a precarious immigration status would actually file a complaint, even after being subjected to extreme mistreatment by Border Patrol agents. In addition, many victims of abuse do not have the resources and/or linguistic ability to navigate CBP’s website and actually file a complaint. These assertions are supported by several reports and academic studies which find that approximately one-in-ten migrants report physical abuse while in U.S. custody. However, even with these limitations, the data offer interesting insights into how CBP operates when it comes to agents’ actions which may precipitate complaints, as well as the handling and resolution of complaints themselves.

First and foremost, this analysis reveals that CBP officials rarely take action against the alleged perpetrators of abuse. Among cases in which a formal decision was issued, 97 percent resulted in “No Action Taken.” This is not to suggest that all of these cases had merit and should have resulted in formal action being taken against particular Border Patrol agents. However, given that several other studies have found strong evidence of systemic abuse at the hands of Border Patrol agents, it is very likely that at least some of these cases did indeed have merit. On average, CBP took 122 days to arrive at a decision when one was made. Moreover, of the 809 complaints, 324 (40 percent) were still “pending investigation” when the complaint data were provided to the Immigration Council. This amounts to powerful evidence of a serious lack of accountability and transparency within CBP.

The Complaints and Their Characteristics

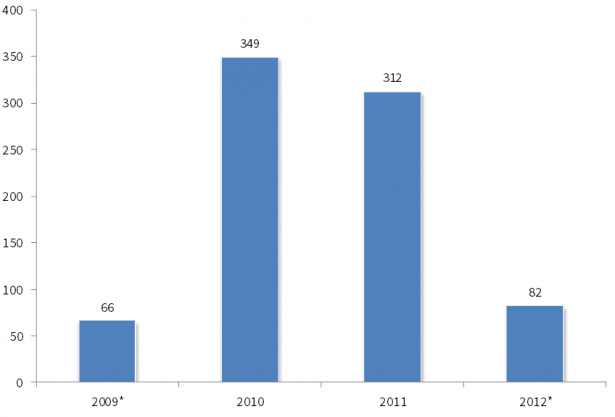

CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs provided the Immigration Council with a total of 809 complaints that were filed against U.S. Border Patrol agents in all nine southwestern Border Patrol sectors between January 22, 2009, and January 5, 2012. Data on complaints were not provided for the first three months of Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 (October, November, and December), nor the last eight months of FY 2012 (January-September). Partial data were provided for the month of January in both FY 2009 and FY 2012 {Figure 1}.

Figure 1: Complaints Filed, FY 2009-2012

Fiscal Year

Source: FOIA Request, American Immigration Council.

* Data provided for only part of year.

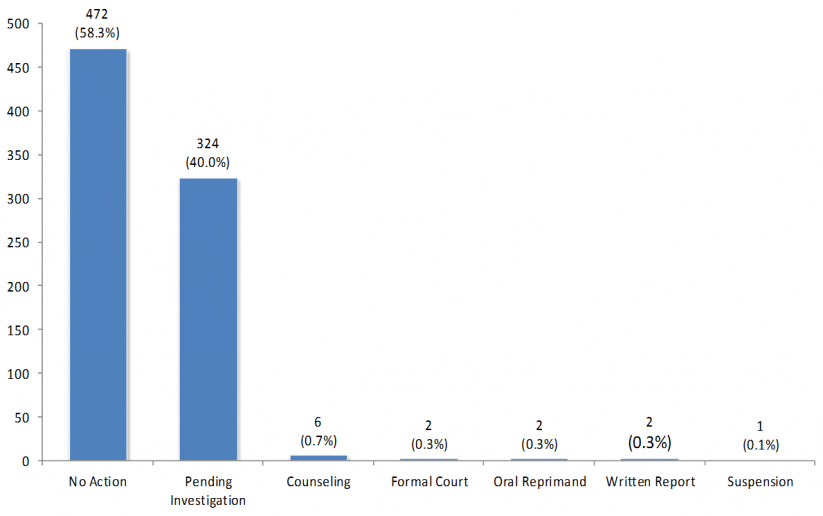

According to the data provided by CBP, “physical abuse” was the most prevalent reason for a complaint, occurring in 40 percent of all cases, followed by “excessive use of force” (38 percent). “Unspecified abuse” (e.g. mentions of “misconduct,” “abuse,” or “mistreatment”) account for 13 percent of cases, while “other” (e.g., inadequate conditions or racial profiling) represents only about three percent of complaints. “Improper searches” or “inappropriate touching”—usually forcing a person to strip—are cited in about two percent of cases. “Sexual abuse” and “medical issues” (withholding of medical treatment) were each cited in less than one percent of all complaints {Appendix Table 1}.

The allegations contained within the complaints encompass many forms of abuse. The bullet points below provide specific examples of the types of mistreatment highlighted in complaints, the Border Patrol Sectors in which the alleged mistreatment occurred, and the outcome of the complaints, if any. For instance:

- “BPA [Border Patrol Agent] allegedly hit a UDA’s [Undocumented Alien’s] head against a rock causing a hematoma.” (Tucson Sector—Counseling)

- “Mexican Citizen alleges BPA physically abused her as she was trying to go back to Mexico.” (San Diego Sector—Formal Court)

- “BPA allegedly kicked female during apprehension causing her to miscarry.” (El Paso Sector—No Action Taken).”

- “A minor alleged he was physically forced by a BPA to sign a document.” (Tucson Sector—No Action Taken).”

- “A UDA alleges a BPA who arrested him stomped on his back after he had lain on the ground.” (Rio Grande Valley Sector—No Action Taken).

- “Allegedly having a relationship with an illegal alien/forcing female aliens to have sex.” (El Centro Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “Unknown BPA from the Laredo Section kicked already handcuffed alien.” (Laredo Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “Alleges that BPAs beat him with a baton and pepper sprayed him.” (San Diego Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “BPAs allegedly denied a UDA water; touched/treated female UDAs inappropriately.” (Tucson Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “Juvenile UDA alleges a BPA pepper sprayed her, hit her in the back; threatened to throw a bomb at her.” (Rio Grande Valley Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “A UDA alleges BPAs stripped him and left him naked in a cell, called him ‘faggot and homo,’ took his DL [Driver’s License].” (El Centro Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “BPA allegedly hit an undocumented juvenile with the butt of his flashlight; grabbed his throat. Calexico, CA.” (El Centro Sector—Pending Investigation)

- “Improper strip search of a driver at a Border Patrol checkpoint.” (El Paso Sector—Written Report)

- “Alleges an unidentified BPA stated ‘Don’t move or I’ll kill you’ as he was being arrested.” (Rio Grande Valley—No Action Taken)

- “Alleged excessive use of force by BPA during an arrest of an alien.” (Rio Grande Valley—Suspension)

Nearly 97 percent of the alleged perpetrators of abuse were U.S. Border Patrol agents, while the remaining 3 percent were Border Patrol supervisors. Among those cases in which the sex of the victims was known, nearly 77 percent were male and 23 percent female. In comparison, 85.6 percent of all U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions were of males and 14.4 percent were of females between FY 2009 and 2012. Therefore, females appear to be overrepresented among complainants. Nevertheless, these figures should be interpreted with caution given that sex was missing in nearly half of the 809 cases. As opposed to the data on sex, information on whether or not the victim was a juvenile appeared to be reported systematically. Overall, juveniles made up 7.2 percent of all complainants during the time period examined. This percentage is strikingly consistent with apprehension figures. Between FY 2009 and 2012, juveniles represented 7.3 percent of all individuals apprehended by the Border Patrol {Appendix Table 1}.

Most Complaints Occurred in Tucson, the Rio Grande Valley, and San Diego

There was substantial variation between U.S. Border Patrol sectors in terms of where complaints were filed. The highest number of complaints were filed against agents in the Tucson Sector (279), followed by the Rio Grande Valley Sector (167), and then the San Diego Sector (132). Collectively, these three sectors account for 71.4 percent of all complaints filed between January 22, 2009 and January 5, 2012 {Figure 2}.

Figure 2: Complaints Filed by Border Patrol Sector

Source: FOIA Request, American Immigration Council.

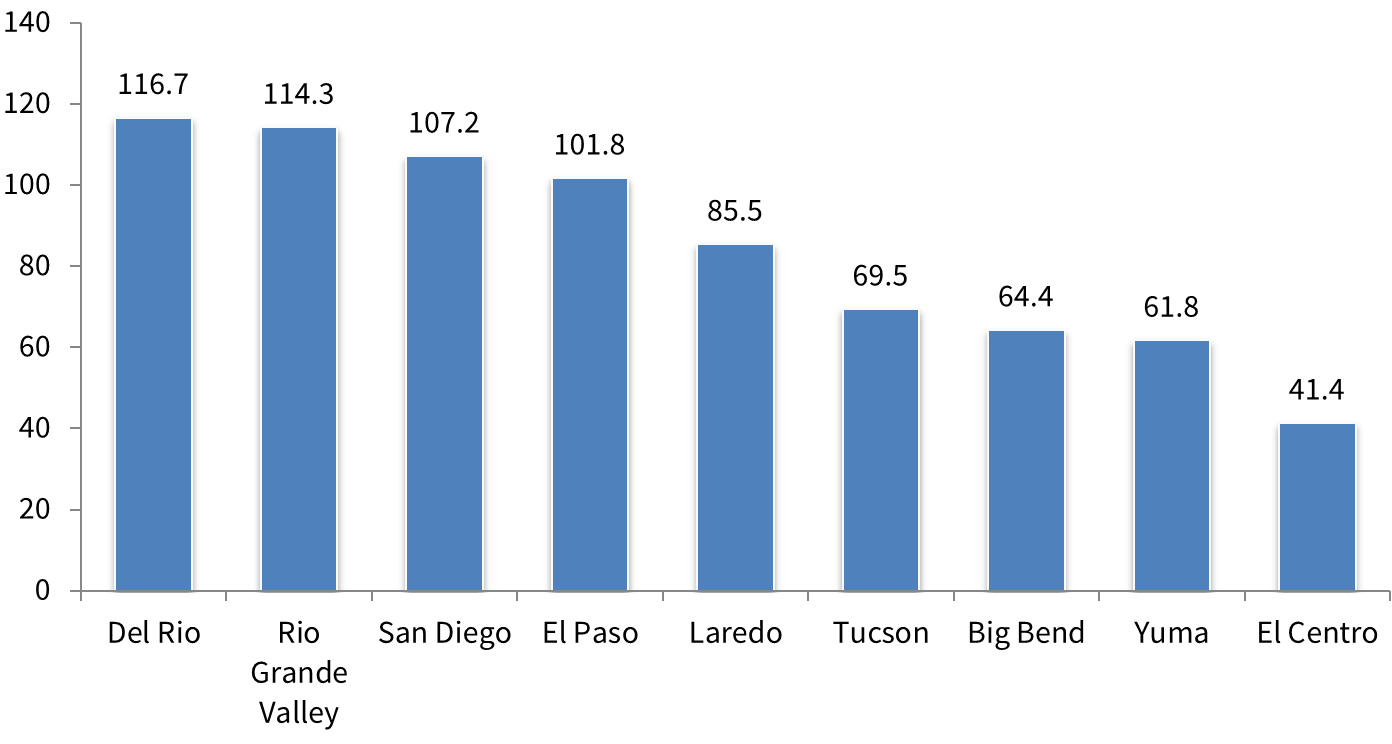

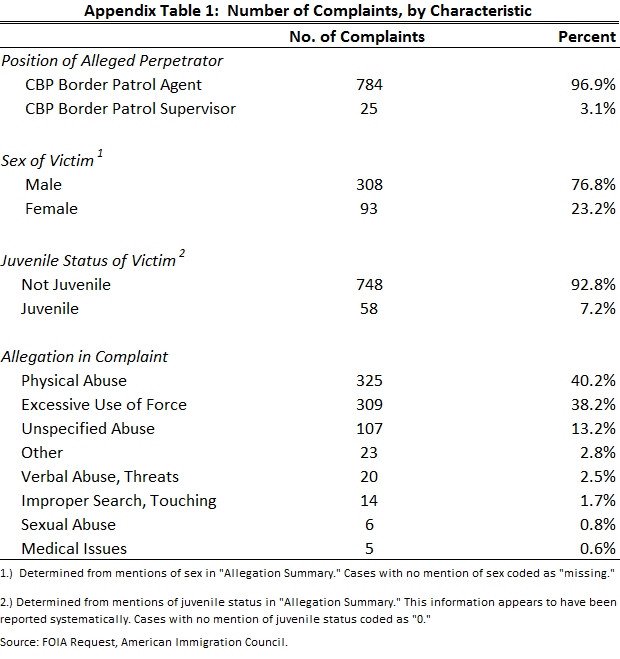

Not surprisingly, more complaints were filed in sectors with higher levels of unauthorized immigration. As a result, “complaint rates,” rather than the raw numbers of complaints, provide a more accurate picture of the state of affairs along the southwestern border by accounting for differences in migration flows through a particular sector. After taking apprehensions into account, the highest rates of complaints in FY 2010-2011 were in the Del Rio Sector (116.7 complaints per 100,000 apprehensions), Rio Grande Valley Sector (114.3), and San Diego Sector (107.2). In comparison, the Tucson Sector had a complaint rate of 69.5. At the other extreme, the El Centro Sector had a complaint rate nearly a third or fourth of the size of the Del Rio, Rio Grande Valley, and El Paso sectors during this time period {Figure 3 and Appendix Table 2}.

Figure 3: Complaints per 100,000 Apprehensions, FY 2010 & 2011

Source: FOIA Request, American Immigration Council.

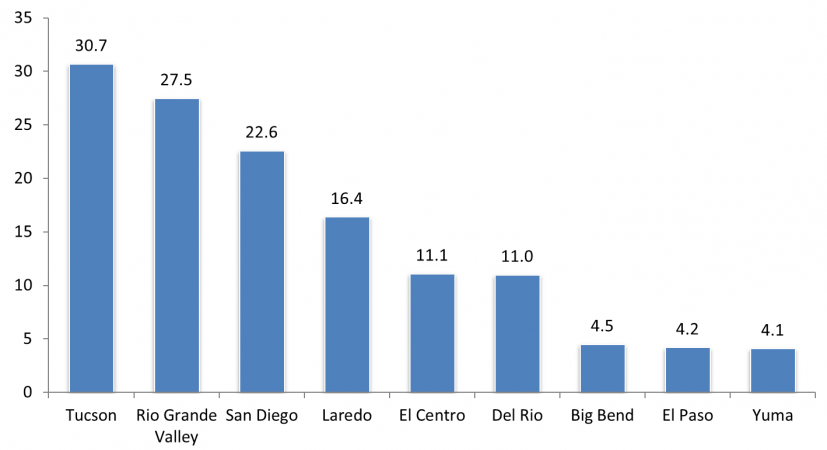

Similar patterns emerge when complaint rates are calculated in terms of the number of Border Patrol agents in each sector. The highest complaint rates were in the Tucson Sector (30.7 complaints per 1,000 agents), Rio Grande Valley Sector (27.5) and San Diego Sector (22.6). At the other end of the continuum were Yuma Sector (4.1), El Paso Sector (4.2), and Big Bend Sector (4.5) {Figure 4 and Appendix Table 2}.

Chronic Inaction by CBP

Among the 809 formal complaints filed against the agency, 472 (58.3 percent) resulted in “No Action Taken,” while 40 percent of complaints (324) were still being investigated when the Immigration Council received the data in response to the FOIA request. Six complaints resulted in counseling, two led to court proceedings against the perpetrator, two led to an oral reprimand of the accused, and an additional two resulted in a written report. Only one resulted in suspension of the perpetrator of the abuse. In other words, among the 485 complaints in which a formal decision was made, “No Action Taken” represented 97 percent of all outcomes, with the average amount of time taken to arrive at a decision being 122 days. Among the cases that were still “Pending Investigation,” the average number of days between the date the complaint was filed and the last record date provided in the data set was 389 days.

Figure 4: Complaints per 1,000 Agents, FY 2010 & 2011

Source: FOIA Request, American Immigration Council.

Conclusions and Recommendations

One of the most revealing findings of this report concerns the prevailing lack of action taken by CBP officials in response to the complaints received. This indicates issues of both effectiveness and efficiency regarding the way in which CBP handles complaints. Moreover, there is a clear need for a stronger system of incentives (both positive and negative) for Border Patrol agents (and all CBP officers) to obey the law, respect legal rights, and refrain from abusive conduct. In order to do that, the complaints process should not only be centralized, but complaints should also be processed more quickly and carefully reviewed. Because of the seriousness of the issues involved, an external review of the complaints filed against CBP is essential.

In terms of geographical distribution of complaints, some border sectors appear to register higher complaint rates than others. During the time period studied, more than one in three complaints filed against Border Patrol agents were directed at agents in the Tucson Sector. However, after taking numbers of apprehensions and Border Patrol agents into consideration—the former of which is often used as a proxy for unauthorized migration flow—complaint rates were highest in the Rio Grande Valley, San Diego, Del Rio, and Tucson sectors. In fact, the complaint rate per apprehensions in the Rio Grande Valley and Del Rio Sectors were more than one-and-a-half times higher than in the Tucson Sector. Of course, we cannot infer a direct association between occurrences of abuses and filing of complaints. It is possible, for instance, that NGOs in some locations do a better job of disseminating information about the complaint process. However, CBP should pay particular attention to the sectors where the complaints are more heavily concentrated.

We also found that 78 percent of allegations against Border Patrol agents were for “physical abuse” or “excessive use of force.” This, of course, could stem from the fact that individuals who suffer more extreme types of abuse are more likely to report it. In any event, the existence of so many complaints regarding physical abuse or excessive use of force reveals that the nature of behaviors reported is indeed serious, and, therefore, the agency should give these complaints the attention they deserve.

Moreover, it is essential that DHS streamline complaint processes into a unified procedure. This would allow DHS to readily review complaints filed with the OIG, JIC, CRCL, and CBP local sector offices and ports of entry, thereby presenting a clearer picture of any problems. It is also crucial that communications regarding complaints be streamlined. Individuals who file complaints, or organizations that file complaints on behalf of individuals, should be informed of the status of the complaints throughout the review process. In addition, complaints should be used by the agency as an opportunity to inform training and promotion of employees as well as improve the performance of its personnel.

Aside from specific sanctions that may be adopted as a result of the review, reports of well-founded complaints should be made available to supervisors, who can develop and implement appropriate performance improvement plans where necessary. In other words, the lessons from the complaints review should be actively shared with key CBP personnel in order to foster a change of culture within the agency. Finally, it is important for CBP to become more transparent, especially considering the magnitude of taxpayer resources allocated to the agency.

Figure 5: Complaints by Decision/Action

Source: FOIA Request, American Immigration Council.

Appendix Tables

We can't let the government keep us in the dark.

Join us in demanding transparency and holding them accountable in court to protect our democracy.

Donate Now