- Fact Sheet

Immigrants and Families Appear in Court

Setting the Record Straight

Published

Immigrants placed into removal proceedings and told to appear in immigration court face a unique penalty for missing court. Unlike criminal court, where a missed court appearance usually results in a judge issuing a warrant for the defendant’s arrest, an immigrant who misses even a single court hearing is generally ordered deported “in absentia” (Latin for “in absence”).

This fact sheet presents studies and analyses on immigrants’ “appearance rate” in court (the rate at which immigrants appear for court hearings). The fact sheet further contrasts appearance rate with “in absentia rate,” a separate and distinct measurement used by the government, which the government and the media often confuse for appearance rate.

Do Immigrants Appear in Court?

Comprehensive analyses of the government’s own data show that in the vast majority of situations, immigrants placed into removal proceedings appear for all of their court hearings.

Even a person who misses a hearing by accident can be ordered removed “in absentia.” A judge may only overturn this “in absentia removal order” if the government failed to notify the immigrant of the hearing, or if the immigrant shows that “exceptional circumstances” led to the failure to appear. Establishing “exceptional circumstances” can be difficult. Courts have refused to overturn removal orders in many circumstances in which the person did not deliberately miss court, where the reasons for missing court were as diverse as a car breaking down, late arrival coupled with long security lines, unusually bad traffic, or a mistaken belief that a hearing was scheduled for the afternoon and not the morning.

Possibly due to the severe consequences of failure to appear, immigrants are highly likely to appear in court. Analysis of data from the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), which oversees the immigration courts, shows that in the vast majority of cases, only 14-23 percent of immigrants scheduled to appear in immigration court missed a hearing and were ordered removed in absentia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. What Percent of Immigrants Not Held in Government Custody Appeared for Court?

|

Group and Time Period Covered by Study or Dataset |

Appearance Rate in Immigration Court |

Appearance Rate if Immigrant Represented by Attorney |

|---|---|---|

|

All immigrants placed in removal proceedings from Fiscal Year (FY) 2008 to June 2019 |

83 percent |

97 percent |

|

Families released from ICE family detention centers, |

86 percent |

97 percent |

|

Non-family individuals released from ICE detention, |

81 percent |

96 percent |

|

Families placed on expedited Family Unit Docket, September 2018 to May 31, 2019 |

81 percent |

99 percent |

|

Families placed on Adults with Children docket, April 2014 to May 2018 |

77 percent |

98 percent |

|

Juveniles placed in removal proceedings, FY 2005 to June 2019 |

83 percent |

98 percent |

Source: Author’s analysis of publicly available data and literature. See endnotes for details.

Studies also show that families are not significantly more likely to miss court than individual adults or unaccompanied children. For example, one study of EOIR data revealed that families released from family detention centers between 2001 and 2016 appeared in court 86 percent of the time, compared to 81 percent for all immigrants released from detention centers over that period. Asylum-seeking families who had representation and were released from detention had even higher appearance rates.

Studies also show a significant link between representation and appearance in court. Having access to an attorney means immigrants have someone who can help them navigate an unfamiliar system, including helping ensure they appear in court. Once immigrants manage to obtain a lawyer, they show up for all court hearings in the overwhelming majority of cases, with appearance rates of 96 percent or higher for every group (see Figure 1).

Of course, many people miss court through no fault of their own. There are serious barriers that can contribute to someone not appearing in court, such as lack of notice; government errors in providing notice; physical, geographical and language obstacles; trauma and mental health; and lack of legal representation.

For these reasons, a significant number of removal orders for failure to appear are later overturned by an immigration judge for lack of notice or “extraordinary circumstances.” A 2018 study of families ordered removed for missing court demonstrated that attorneys were able to overturn 44 out of 46 in absentia removal orders issued to asylum-seekers’ families. In one case, a family member received two pieces of mail on the same day—a letter telling the person to appear for a court proceeding with a hearing date which had already passed, and an in absentia removal order for missing that court date.

Significant Flaws Exist with the Government’s Measurement of Failures to Appear

Given that studies consistently show a high appearance rate for those in removal proceedings, why does the government insist that there is an epidemic of immigrants skipping court and “disappearing” into the United States? Boiled down, the most basic answer is: the government does not measure the percent of immigrants failing to appear in court. Instead, it uses an alternate, “completion-based” method which significantly overstates the prevalence of in absentia orders of removal for failure to appear in court.

Every year EOIR publishes data on what it calls the “in absentia rate.” This rate is calculated by determining what percent of “case completions” (a decision in an immigrant’s case, such as a grant of relief or an order of removal) occurred because the immigrant missed court. For example, if a judge ordered one person removed for failure to appear and granted another person relief from removal, the “in absentia” rate would be 50 percent—one order of removal for missing court out of two completions.

This approach means that people who are showing up to court during their case, but have not received a final decision, are not factored into the equation. Cases often require multiple hearings over the course of years before a “completion,” which means that EOIR’s statistic neglects to account for the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who have appeared in court, but whose cases are not yet complete. EOIR’s “in absentia rate” gives the false impression that more immigrants miss court than actually do because cases where an immigrant fails to appear at the first hearing take significantly less time to complete than a case where the immigrant appears diligently for years before a final decision.

Even though EOIR’s “in absentia rate” is not a full measure of appearance rates, DHS has cited “in absentia” rate figures in ways that falsely imply that it is. For example, in June 2019, Acting DHS Secretary Kevin McAleenan testified in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee that 90 percent of families placed on EOIR’s recently-created expedited “Family Unit Docket” failed to appear in court. But McAleenan was wrong; an independent analysis of EOIR data on the Family Unit Docket showed that as of May 31, 2019, 81 percent of families on the docket had appeared for all scheduled hearings since September 2018. When families were represented, 99 percent had appeared in court for all hearings.

So why the difference? McAleenan appears to have confused EOIR’s “in absentia rate” for the rate at which families missed court. This citation of the Family Unit Docket’s “in absentia rate” as if it were the appearance rate provides a cautionary example of why citation to EOIR’s “in absentia rate” can be problematic.

The expedited Family Unit Docket was created by EOIR in November 2018 with the intention of expediting cases of recently-arrived families. Because the docket has only existed for a matter of months, and because cases in immigration court often take months or years to complete, only a small fraction of cases placed on the docket have reached an ultimate decision on the merits of a case.

Figure 2. Perils in Citing the Family Unit Docket’s “In Absentia” Rate

Data from EOIR shows that out of 64,362 cases placed on the docket in 10 cities since September 2018, over 74 percent of cases are still pending (47,408). Of the cases completed as of June 2018, 3,371 were completed because a judge issued a decision on the merits of the case, while 13,583 were completed because the immigrant failed to appear in court (Figure 2).

Thus, even though 81 percent of families placed on the docket have appeared in court, the “in absentia” rate reported by EOIR would be 82 percent. This example shows how the government’s methodology for reporting failures to appear can create the wrong impression about how often people appear in court.

How Should Appearance Rates Be Calculated?

Alternate methods should be used to calculate the “in absentia rate” because EOIR’s current method does not fully reflect the percent of immigrants who appear in court.

A better approach is a cohort-based methodology, which looks at the percent of people placed into removal proceedings each year who have been ordered removed for missing court. By focusing on a group of people and tracking them throughout the entire multi-year process of immigration court, a cohort-based method avoids harmful abstractions. Unlike EOIR’s completion-based methodology, looking at groups of people over time better shows what percent of immigrants appeared in court.

Using a cohort-based method reveals that in every year since 2007, fewer than 25 percent of people placed on the non-detained docket were ordered removed for missing court (Figure 3). Since 2015, over 80 percent of all immigrants placed into removal proceedings have appeared for their court proceedings and avoided an order of removal for missing court.

Figure 3: Percent of Non-Detained Cases with a Final Order of Removal for Missing Court

Note: Years reflect the fiscal year case originally filed with immigration court, through May 2019.

Source: TRAC, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court (last accessed July 2019). Data on file with author.

This cohort-based method shows that even with more asylum-seekers arriving at the border in the past five years, immigrants placed in removal proceedings are still highly likely to appear in court. And despite record levels of families arriving at the border in FY 2019, orders of removal for missing court remain relatively uncommon.

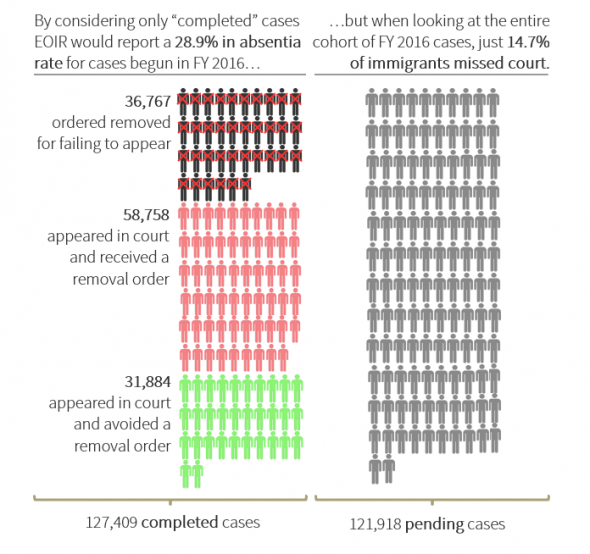

Given the concerns noted above, EOIR should immediately abandon the use of its completion-based “in absentia” statistics, or at the very least clarify that such statistics do not represent appearance rates. As shown in Figure 4, the cohort-base methodology provides a significantly more accurate way of measuring the rate at which immigrants appear in court.

Figure 4. Cohort-Based Methodology Compared to EOIR’s Completion-Based “In Absentia Rate”

Using cases begun in Fiscal Year 2016 as a case study

Source: Author’s analysis of data on “never-detained” and “released” cases begun in FY 2016, through June 2019. TRAC, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court (last accessed July 2019).

EOIR’s own data demonstrates in other ways that there is no crisis of immigrants failing to appear in court. In FY 2018, 46,051 orders of removal for missing court were issued, despite DHS filing a record high of 314,316 cases in immigration court that year and amid a record high backlog of 794,316 cases.

Good policy comes from good data. The government’s reliance on “completion-based” reporting methods distorts appearance rates and gives the false impression that there is an epidemic of failures to appear in immigration court. But as long-term studies show, when you track people from start to finish, the vast majority of immigrants appear in court.

What Could Further Improve Appearance Rates?

Given immigrants’ likelihood of appearing in court, there is little evidence for the government’s frequent assertion that detention is necessary to ensure appearance in court.

Instead, focus should be on ensuring that immigrants who want to appear in immigration court have the opportunity to do so. This could be achieved through initiatives like the Family Case Management Program, an innovative program which achieved a 99 percent compliance rate with immigration court appearances through the use of community support and supervision. The immigration courts could also adopt simple methods to help ensure that people don’t miss court. Studies have shown that sending text messages or email reminders can have a significant effect on ensuring appearance in court.

Improved access to counsel is also key in further increasing immigrants’ appearance rates. As Figure 1 shows, when immigrants are represented, they appear in court over 97 percent of the time. Having an attorney can help immigrants understand the complex and confusing immigration court system and navigate around common pitfalls that can lead to an order of removal for missing court. Indeed, immigrants with attorneys fair better at every stage of the court process. Improving access to counsel would almost certainly have a significant effect on ensuring that every immigrant who wants their day in court has the opportunity to get one.

The government should also focus on fixing procedural errors which lead to immigrants not receiving notice of their court hearings. Even though the immigration system is faced with historic case backlogs, the government’s failure to properly file notices to appear with correct address information and the court’s well-documented failure to send hearing notices in a timely manner have created significant obstacles to immigrants receiving a fair day in court.

These obstacles have become especially problematic in light of EOIR’s expedited Family Unit Docket, where the accelerated process has created more opportunities for government error. Some families placed on the docket report that the first document they received from the immigration court was an order of removal for missing a court date about which they never received notice. Given the high potential for error, EOIR should carefully review docketing practices for cases placed on the Family Unit Docket and instruct judges to hold the government to its burden of proving by “clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence” that a family received notice of a hearing before ordering anyone removed for missing court.

At present, the only way for individuals to determine whether a court date has been set is to call 1-800-898-7180 and listen to an automated message available only in English and Spanish. In addition, those in removal proceedings can only change the address the court has on file by mailing a form in English to the correct immigration court. This thoroughly outdated system creates innumerable opportunities for well-meaning individuals to fall through the cracks. It is far past time for EOIR to modernize these systems and focus its resources on ensuring that no person ever misses court through government error.

We can't let the government keep us in the dark.

Join us in demanding transparency and holding them accountable in court to protect our democracy.

Donate Now