- Fact Sheet

The Future of a Generation: How New Americans Will Help Support Retiring Baby Boomers

Published

The United States is in the midst of a profound demographic transformation that will long outlast the current economic downturn. In 2011, the first of the baby boomers—Americans born between 1946 and 1964—turned 65 years old. There are 77 million baby boomers, comprising nearly one quarter of the total population, and their eventual retirement will have an enormous impact on the U.S. economy. This daunting fact is central to the January 2012 employment and labor force projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). As the BLS projects, the retirement of the baby boomers will slow labor force growth significantly over the coming decade. Yet, at the same time, demand will grow for new workers to take the place of those who retire from the labor force, as well as for both highly skilled and less-skilled healthcare workers to look after the growing ranks of elderly Americans. In addition, the Social Security and Medicare programs will be called upon to serve a rapidly growing number of older Americans, which will leave American taxpayers hard pressed to fund those programs with their tax dollars.

In short, there will be growing demand within the U.S. economy for younger workers and taxpayers. For two demographic reasons, more and more of these workers and taxpayers will be immigrants and the children of immigrants. First, immigration fuels more than two-fifths of U.S. population growth, and immigrants tend to be younger than the native-born population. Second, immigrant communities tend to have higher birth rates, so they comprise a disproportionately large share of the next generation of workers. It is this combination of continued immigration and high fertility that explains the rapidly rising number of young Latinos in the U.S. population and labor force. Conversely, the non-Latino white population, which is fed by very little immigration and has low fertility, has seen its share of the population and labor force decline, while its average age rises. Given these trends, and given the size of the predominantly white, native-born baby boom generation that is now heading into retirement, the BLS projections point to an inescapable conclusion: immigrants and the children of immigrants will play increasingly important roles within the U.S. economy as workers and taxpayers for decades to come.

Aging on a Global Scale

The United States is not the only country confronting the challenges of an aging population. As fewer children are born and more adults live longer, the population of the entire world is rapidly growing older. The elderly (people age 65 and over) will soon outnumber children under the age of five for the first time in history. By 2030, there will be 1 billion elderly people, accounting for one-eighth of the global population. The “oldest” country by far is Japan, where nearly one-quarter of all people are elderly, followed closely by Italy and Germany. Although Japan, Europe, and the United States are experiencing the most pronounced aging of their populations, other countries around the globe are growing older as well, including China, India, Mexico, and Brazil. More and more nations are grappling with the economic implications of declining labor-force growth coupled with increasing demands upon healthcare, pension, and social insurance systems.

Aging in the United States

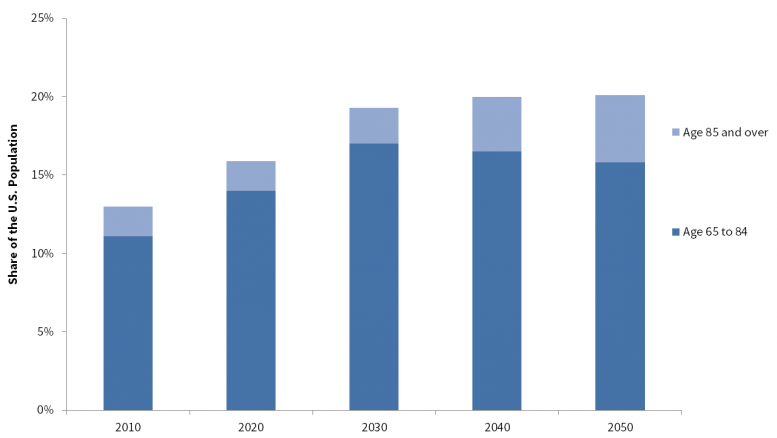

Although the United States is not aging as rapidly as Japan, it is still aging fast. The elderly share of the U.S. population grew from only 8.3 percent in 1950 to 13.1 percent in 2010. It is projected to reach 19.9 percent by 2030 (after the last of the baby boomers have turned 65), and will then inch up to 21.2 percent by 2050. In contrast, the share of the population consisting of working-age adults and children will decline over the next few decades {Figure 1}.

Figure 1: Age Distribution of U.S. Population, 1950-2050

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision.

In terms of sheer numbers, the elderly population of the United States will more than double in size in only four decades. The number of people age 65+ will rise from 40.2 million in 2010 to 88.5 million in 2050. The highest rate of increase will be among the “oldest of the old”: those 85 and older, who tend to require the most healthcare services. This group will grow in size from 5.8 million in 2010, to 8.7 million in 2030, to 19 million in 2050—or one-fifth of the elderly population {Figure 2}.

Figure 2: Elderly Share of the U.S. Population, 2010-2050

Source: Grayson K. Vincent and Victoria A. Velkoff, The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050, P25-1138 (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, May 2010), p. 10.

The U.S. population would be aging even more rapidly if not for the demographic impact of immigration. Because immigrants tend to be younger than native-born Americans—and to have higher rates of labor-force participation—they mitigate the impact of aging among the native-born population and workforce. In 2010, roughly 80 percent of immigrants were “working age” (18 to 64), compared to only 60 percent of the native-born population. As a report from the U.S. Census Bureau points out, “the country’s aging is slowed somewhat by immigration of younger people.” Demographer Dowell Myers estimates that current levels of immigration will temper the aging of the U.S. population substantially over the next two decades, slowing the increase in the “old-age dependency ratio”—the number of elderly per 1,000 working-age individuals—by more than one-quarter.

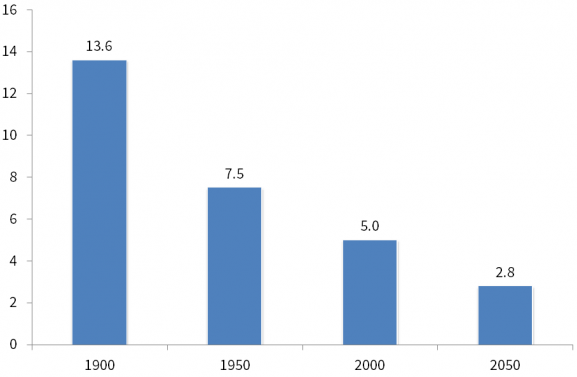

However, neither current levels of immigration nor current birthrates are sufficient to fully compensate for the retirement of the baby boomers. Immigration and new births notwithstanding, the elderly population is projected to grow far more quickly than the working-age population. The number of working-age adults for every elderly person in the United States declined from 13.6 in 1900 to 7.5 in 1950 to 5.0 in 2000. It will drop to only 2.8 by 2050 {Figure 3}. This represents an enormous fiscal and economic burden upon taxpayers and workers. Over the coming decades, the United States will face an escalating need for new taxpayers to help fund Social Security and Medicare, new workers to take the place of retirees, and new healthcare providers to care for the elderly.

Figure 3: Number of Working-Age Adults Per Person Age 65 or Over, 1900-2050

Source: See endnotes 20-23.

Immigration, Social Security, and Medicare

The two taxpayer-funded federal programs upon which the vast majority of elderly Americans rely are Social Security and Medicare. Social Security “provides retirement, disability, and survivor benefits to qualifying workers and their families. These benefits are funded from two trust funds: the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund and the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund.” Roughly 54 million people were receiving Social Security benefits as of December 2010. Approximately 69 percent of those were retired workers and their spouses and children, while the rest were survivors of deceased workers, and disabled workers and their spouses and children. The Social Security Administration paid out $701.6 billion in benefits during 2010.

Medicare is an insurance program that pays for healthcare services for elderly and disabled beneficiaries. It is funded from two trust funds: the Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund, which “covers inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing care, and home health and hospice care,” and the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund, which “covers physician services, outpatient services, and some home health and preventive services.” In 2010, Medicare provided $516 billion in benefits to 47.5 million people (39.6 million elderly and 7.9 million disabled).

Given the impending retirement of the baby boomers, the financial outlook for Social Security and Medicare is bleak. Expenditures on these programs are projected to reach nearly 15 percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product by 2050—up from 4 percent in 1970. In 2010, Social Security for the first time collected less in tax revenue than it paid out in benefits. According to the Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees, Medicare’s HI trust fund is projected to become insolvent in 2024, “after which tax income would be sufficient to pay 90 percent of HI costs, declining to 76 percent in 2050, and then increasing to 88 percent by 2085.” Social Security’s OASI and DI trust funds are projected to run dry in 2036, at which point “continuing tax income would be sufficient to pay 77 percent of scheduled benefits in 2036 and 74 percent in 2085.”

Immigration can not make up for the funding shortfalls of Social Security and Medicare, but it can make those shortfalls less severe. Both Social Security and Medicare need new, younger workers to pay into the programs with their tax dollars. With the baby boomers set for retirement over the next few decades, and with fertility rates low among the native-born, many of these new workers and taxpayers will be immigrants. Many of them will be the children of immigrants as well. As of 2009, nearly one-quarter (23 percent) of all people age 17 and younger in the United States had at least one immigrant parent. Children of immigrants are the fastest growing demographic group within the U.S. population. When these children become adults and join the workforce, the taxes they pay—as well as the taxes their immigrant parents pay—will help to sustain Social Security and Medicare.

Immigration and the Healthcare Workforce

The aging of the population will increase the demand for workers in a wide range of industries and occupations as retiring native-born workers leave the labor force. The BLS projects that there will be 54.8 million job openings from 2010 to 2020, of which 21.1 million will result from economic growth, while 33.7 million will arise from the need to replace workers who either retire or move into different occupations. In fact, “in four out of five occupations, openings due to replacement needs exceed the number due to growth.”

The demand for healthcare workers will remain particularly strong due to the mounting healthcare needs of the burgeoning elderly population. According to the BLS, “the health care industry added 428,000 jobs throughout the 18-month recession from December 2007 until June 2009 and has continued to grow at a steady rate since the end of the recession.” Moreover, “the health care and social assistance industry is expected to be the most rapidly growing sector in terms of employment” between 2010 and 2020. The BLS projects that, between 2010 and 2020, employment will increase by 34.5 percent in healthcare support occupations and 25.9 percent in healthcare practitioner and technical occupations. There is a growing demand for workers in long-term care in particular as more of the elderly require nursing home care, residential care, adult day care, and home care.

Immigrants fill, and will continue to fill, many of these jobs. As of 2010, immigrants comprised roughly 14 percent of workers in healthcare practitioner and technical occupations (which include physicians, pharmacists, dentists, physical therapists, and clinical laboratory technicians) and 18 percent in healthcare support occupations (which include home health aides, nursing aides, medical assistants, and dental assistants). Given the demographic trends at work within U.S. society, it is likely that immigrants and their children will fill even more jobs in healthcare in coming decades as retirements mount and the healthcare demands of the elderly population increase.

Immigration and Our Demographic Future

When it comes to the impending retirement of the baby boomers, U.S. policymakers must think beyond the current economic downturn and look at the decades that will follow. In doing so, they must recognize two fundamental truths about the economics of immigration to the United States. First, immigration has always been an engine of growth for the U.S. economy. Immigrants—and, eventually, their children as well—fill gaps in the labor force, create new businesses, and pay into the tax system. Second, despite the economic importance of immigrants, the U.S. immigration system remains stubbornly oblivious to the forces of supply and demand that actually drive immigration. Ours is a system of arbitrary numerical caps that bear little relationship to economic reality. Policymakers would be wise to take a much more purposeful and strategic approach to immigration: legally admitting those immigrants who can help take the place of retiring baby boomers in the labor force, care for the growing ranks of elderly Americans, and shore up the Social Security and Medicare systems with their tax dollars.

Help us fight for immigration justice!

The research is clear – immigrants are more likely to win their cases with a lawyer by their side. But very few can get attorneys.

Introducing the Immigration Justice Campaign Access Fund.

Your support sends attorneys, provides interpreters, and delivers justice.

Immigration Justice Campaign is an initiative of American Immigration Council and American Immigration Lawyers Association. The mission is to increase free legal services for immigrants navigating our complicated immigration system and leverage the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted by our country’s immigration policies to inform legal and advocacy strategies. We bring together a broad network of volunteers who provide legal assistance and advocate for due process for immigrants with a humane approach that includes universal legal representation and other community-based support for individuals during their immigration cases.