- Fact Sheet

The “Migrant Protection Protocols”

Published

In December 2018, the Trump administration announced the creation of a new program called the “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP 1.0)—often referred to as the “Remain in Mexico” program. The program went into effect in January 2019 and was used to send nearly 70,000 migrants back to Mexico. Citing widespread reports of severe human rights violations and seriously logistical problems caused by the program, the Biden administration suspended, and then terminated, the program after President Biden took office. A “reinstated” Remain in Mexico program returned 7,505 people to Mexico from December 2021 to August 2022 as the result of federal court order which was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court. The government of Mexico has since indicated that it opposes any attempt by the United States to restart a similar program in the future.

Under MPP, individuals who arrived at the southern border and asked for asylum (either at a port of entry or after crossing the border between ports of entry) were given notices to appear in immigration court and sent back to Mexico. They were instructed to return to a specific port of entry at a specific date and time for their next court hearing. MPP was distinct from a separate process known as “metering,” whereby U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials turn asylum seekers away from ports of entry without processing them or providing any specific date or time to return.

MPP did not provide due process to migrants. Representation rates for the people subjected to MPP were exceedingly low. Data suggests that just 7.5 percent of individuals subject to MPP 1.0 ever managed to hire a lawyer, though the true representation rate may be even lower because that number includes individuals who were initially placed into MPP and then were later taken out of the program and allowed to enter the United States.

The lack of counsel, combined with the danger and insecurity that individuals faced in border towns, made it nearly impossible for anyone subjected to MPP to successfully win asylum. By December 2020, of the 42,012 MPP cases that had been completed under MPP 1.0, only 521 people were granted relief in immigration court.

How the Migrant Protection Protocols Were Carried Out

From January 2019, when the MPP process began, through December 2020, at least 70,000 people were returned to Mexico to await court hearings, according to the nonpartisan Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. The exact number of individuals subject to MPP since its inception has never been disclosed by DHS, although the department eventually began posting monthly data on MPP in August 2020 as required by Congress. From December 2021 through October 2022, 7,505 more people were placed into MPP by the Biden administration.

The federal government placed people into MPP at seven U.S. border towns:

-

San Ysidro, CA

-

Calexico, CA (individuals returned to Mexico at Calexico were required to travel to the San Ysidro port of entry for hearings)

-

Nogales, AZ (individuals returned to Mexico at Nogales were required to travel to the El Paso port of entry for hearings)

-

El Paso, TX

-

Eagle Pass, TX (individuals returned to Mexico at Eagle Pass were required to travel to the Laredo port of entry for hearings)

-

Laredo, TX

-

Brownsville, TX

Many individuals were sent to Mexico under MPP at a location far from where they arrived at the border. For example, some families who crossed the border near Yuma, Arizona, were transported by CBP to the Calexico port of entry hundreds of miles away to be returned to Mexico. Similarly, individuals who crossed in the Border Patrol’s Big Bend Sector were transported hundreds of miles and sent back to Mexico in El Paso.

In San Diego and El Paso, individuals who returned for court hearings arrived at the port of entry, were briefly “paroled” into the United States for the purpose of going to court, and then were transferred into the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for transport to the local immigration court. According to a copy of ICE’s MPP Standard Operating Procedures obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, in El Paso individuals were given just one hour after arriving at court to speak with their attorney. In Laredo and Brownsville, individuals who returned for court hearings were taken to “tent courts” built next to the port of entry, where they appeared in front of immigration judges through video teleconferencing equipment.

According to the U.S. government’s “guiding principles” for MPP 1.0, certain groups were considered exempt from the MPP 1.0 process:

-

Unaccompanied children

-

Citizens or nationals of Mexico

-

Individuals processed for expedited removal

-

Individuals in “special circumstances,” including:

-

Individuals with “known physical/mental health issues”

-

Individuals with criminal records or a history of violence

-

Individuals determined by an asylum officer to be “more likely than not” to face torture or persecution in Mexico on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group

The decision to send a person or family back to Mexico under MPP was discretionary and was made by individual CBP officers or Border Patrol agents. Individuals who crossed the border at the same time were sometimes treated differently, with one person sent back under MPP and the other person permitted to seek asylum through the normal process. In some situations, this led to families being separated at the border, with one parent sent back to Mexico and the other parent and the child allowed to enter the United States.

CBP also retained discretion to take any individual out of MPP on a case-by-case basis. In addition, CBP had stated that it did not subject individuals to MPP who were from countries where Spanish is not the primary language (for example, Cameroon or India), although nothing in the MPP “guiding principles” required their exclusion. In December 2019, Acting CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan threatened to end this exemption and send individuals from non-Spanish-speaking countries back to Mexico under MPP, emphasizing that the policy could be changed at any moment. On January 29, 2020, DHS officially announced that it had expanded MPP to Brazilian nationals.

CBP implemented its MPP 1.0 “guiding principles” inconsistently across the border. For example, there were reports of CBP officers sending back individuals with serious medical issues in violation of the guidelines. On December 7, 2020, DHS issued “supplemental guidance” on MPP. The guidance made few substantive changes to the operation of MPP but confirmed a number of troubling practices by which DHS carried out the program, including forcing individuals to wait in Mexico during the course of any appeal of a positive decision in their case.

Under MPP, CBP officers did not ask asylum seekers if they were afraid of returning to Mexico. A person who feared harm in Mexico was required to “affirmatively” assert that fear if they wanted to be taken out of MPP. If an asylum seeker did so, the person had to be referred to an asylum officer for an interview about their fear. Individuals generally were held in CBP custody for these interviews and were not allowed access to an attorney. Some individuals reported being handcuffed throughout the interview process.

Government estimates of the number of people who passed these interviews ranged from 1 percent to 13 percent. After MPP began, some asylum officers who conducted these interviews spoke out about pressure to deny people and send them back to Mexico, calling the interviews “lip service.” The labor union representing asylum officers filed an amicus brief with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals asking the court to strike down MPP as a directive that was “fundamentally contrary to the moral fabric of our nation and our international and domestic legal obligations.”

In December 2019, an internal DHS analysis of MPP 1.0 revealed serious flaws in the screening process that called into question whether asylum seekers were consistently provided even the limited protections available under the program. These flaws included CBP’s reported use of “a pre-screening process that preempts or prevents a role for USCIS [U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services] to make its determination,” and reports that “CBP officials pressure[d] USCIS [asylum officers] to arrive at negative outcomes.”

These findings were supported by a study of 607 people sent back to Mexico under MPP 1.0, which determined that just 40.4 percent of asylum seekers who expressed a fear of returning to Mexico to CBP were given the required fear-screening interview.

Prior to the indefinite suspension of MPP hearings, many individuals were forced to wait months to have their asylum case decided or even receive an initial hearing. During the time these asylum seekers remained in Mexico, it was extremely difficult to obtain counsel. According to an independent analysis of data obtained from the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR)—the office that oversees the immigration courts—roughly 7.5 percent of asylum seekers in MPP had a lawyer. Through the end of December 2020, just 5,285 people subject to MPP had secured lawyers out of 70,467 people who had been placed in MPP proceedings.

Many asylum seekers placed into MPP experienced extreme danger in Mexico. Individuals sent to the Laredo or Brownsville courts had to reside or pass through the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, which the State Department has classified as the same level of danger as Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Many asylum seekers and families were kidnapped and assaulted after having been sent back to Mexico, sometimes within hours of crossing back over the border.

According to Human Rights First, through February 2021 there were at least 1,544 publicly documented cases of rape, kidnapping, assault, and other crimes committed against individuals sent back under MPP. Multiple people, including at least one child, died after being sent back to Mexico under MPP and attempting to cross the border again.

The U.S. government did not provide support to individuals sent back to Mexico, leaving people to fend for themselves. Many were homeless during their time in Mexico. In some locations on the border, the Mexican government created shelters that could house some—but not all—of the people sent back. Private shelters also provided housing for some individuals sent back under MPP. In Matamoros, a tent camp sprang up in 2019 where thousands of asylum seekers eventually resided along the Rio Grande in squalid conditions with no running water or electricity.

Given these conditions, thousands of people subjected to MPP were unable to return to the border for a scheduled court hearing and were ordered deported for missing court. Some missed hearings because the danger and instability of the border region forced them to abandon their cases and go home. Others missed hearings because they were the victims of kidnapping or were prevented from attending because their court paperwork was stolen.

Complicating matters, the Mexican government and the United Nation’s International Organization for Migration provided buses traveling from the U.S.-Mexico border to the Mexico-Guatemala border for individuals who chose to abandon their cases and go home. However, multiple reports indicated that some individuals sent back under MPP were coerced onto these buses and ended up hundreds of miles from the border with no way to get back for their court dates. In total, 44 percent of all people sent back to Mexico under MPP were unable to return to court for a hearing.

The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on MPP

On March 23, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, both DHS and EOIR suspended MPP 1.0 hearings across the border, and the courts that carried out MPP hearings temporarily shut down. From March through July, MPP hearings were periodically re-suspended, each time creating more uncertainty among those still waiting for a court date. Finally, on July 17, 2020, DHS and EOIR formally admitted that the program would be indefinitely suspended during the pandemic.

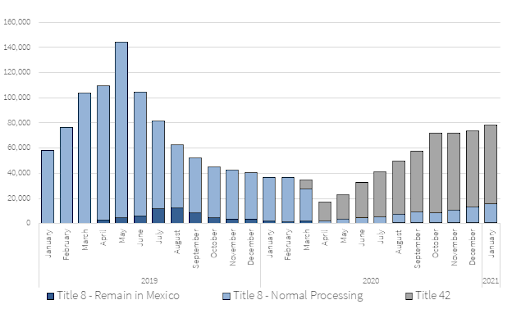

Despite the possibility that those with pending cases might have to wait two to three years in Mexico before a hearing, the Trump administration refused calls to admit those in MPP with pending cases into the United States. In total, CBP subjected over 6,000 people to MPP following the suspension of hearings, sending them to Mexico to wait for an unknown period. During this time, MPP was almost entirely replaced by Title 42, with hundreds of thousands expelled under that policy during Trump’s last months in office (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Enrollments in MPP Compared to Expulsions Under Title 42, January 2019 to January 2021

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection data.

Along with worsening conditions in shelters at the border and pandemic-related restrictions imposed across Mexico, the indefinite suspension of MPP led many people with pending cases to abandon their hope of seeking protection.

Many of those subject to MPP 1.0 returned to their home countries, while others tried to enter the United States again. At least 700 children who were part of families subject to MPP were sent across the border alone by their parents. In total, DHS has said that nearly 25 percent of all people subject to MPP 1.0 eventually tried to cross the border a second time.

Developments Under the Biden Administration

On January 20, 2021, the same day that President Biden took office, DHS suspended all new enrollments in MPP, preventing any new people from being sent back to Mexico.

Beginning in February 2021, the Biden administration began formally winding down MPP. The first phase of this “wind down” involved processing into the United States those waiting in Mexico who had pending MPP cases. This began on February 26, 2021. In order to be processed, individuals first had to be registered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which verified that individuals were eligible for the MPP wind-down. Those in Mexico had to register through “Conecta,” a service set up by UNHCR. Individuals also needed a negative COVID-19 test prior to being processed into the United States.

By early March, the infamous refugee camp in Matamoros had been emptied and nearly everyone inside processed into the United States and allowed to pursue asylum. In June, the Biden administration announced that it would also process individuals subject to MPP who had been ordered deported for missing their court hearings. Over the next five months, just over 13,000 people were processed into the United States.

On August 15, as part of a lawsuit brought by the states of Texas and Missouri, a federal judge ordered the Biden administration to “enforce and implement MPP in good faith until such a time as it has been lawfully rescinded in compliance with the APA [Administrative Procedure Act] and until such a time as the federal government has sufficient detention capacity to detain all [noncitizens] subject to mandatory detention under Section 1255 without releasing any [noncitizens] because of a lack of detention resources.” Despite the extraordinary and unprecedented nature of this decision, which forced the Executive branch to engage in diplomatic negotiations with Mexico, the Supreme Court refused to temporarily halt the order while it went through the appeals process.

Following that decision, in September the Biden administration disclosed that it had begun internal deliberations about reinstating MPP and was engaged in diplomatic negotiations with the government of Mexico, and that no person could be sent back to Mexico without that country’s cooperation. On December 2, 2021, the Biden administration announced that it had reached a deal with Mexico and would be reinstating MPP along the border in the following weeks.

The first returns under a reinstated MPP 2.0 occurred on December 8, 2021, when two men were sent from El Paso, TX, to Ciudad Juárez. In June 2022, the Supreme Court overturned the order which had forced the Biden administration to reinstate MPP. The program was formally ended again in October 2022.

Comparing MPP 1.0 and MPP 2.0

When the Biden administration reinstated MPP in December 2021, it did not revive the program in the same form as it existed under the Trump administration. Instead, the Biden administration made a series of changes, expanding it in some ways and limiting it in others.

Most notably, the Biden administration expanded the group of people who can be placed into MPP. Under MPP 2.0, CBP could apply MPP to all Western Hemisphere nationals (excluding Mexicans), a larger group of people than MPP 1.0, which was limited only to nationals of Spanish-speaking countries and Brazil. This expanded population meant that MPP was applied to Haitians and other Caribbean nationals who were previously exempt under MPP 1.0.

Individuals were placed into MPP 2.0 at the same seven ports of entry that were used in MPP 1.0, and the locations of court hearings remained the same. The initial returns under MPP 2.0 occurred in El Paso, expanded across the border by February 2022. Unlike in the first iteration of MPP, individuals were not eligible for MPP 2.0 if they sought asylum at a port of entry, because Title 42 remained in effect and the ports of entry were shut to asylum seekers at the time.

The first 200 individuals placed into MPP 2.0 in El Paso in December 2021 were all single adults from Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, or Colombia, nationalities which Mexico did not accept for Title 42 expulsions. This was a stark difference from MPP 1.0, which mainly targeted nationals of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. As with MPP 1.0, unaccompanied children were exempt from MPP 2.0.

The most significant change made to MPP 2.0 was an expansion of the process by which someone could be removed from the program due to a fear of persecution or torture in Mexico. Unlike MPP 1.0, in which CBP was forbidden from asking migrants if they had a fear of returning to Mexico, in MPP 2.0 CBP officers were required to ask every person in the program about their fear of returning to Mexico. Unlike MPP 1.0, in which individuals had to prove it was “more likely than not” that they would be persecuted or tortured in Mexico, under MPP 2.0 individuals only had to prove that there was a “reasonable possibility” of persecution or torture in Mexico in order to be exempted from the program. In addition, MPP 2.0 did not actively prevent people from speaking to an attorney during the nonrefoulment interview process, and each person was supposed to be given 24 hours prior to the interview to contact a lawyer.

Data released by DHS relating to people placed through MPP 2.0 reveals that these different screening standards made it significantly more possible for people to be taken out of MPP than during MPP 1.0. In total, out of 12,564 people who CBP screened for possible return to Mexico under MPP 2.0 from December 2021 through August 2022, a total of 5,059 (40%) were exempted.

Throughout the time that MPP 2.0 was in effect, many of the same problems of MPP 1.0 occurred again. Migrants continued to have significant difficulty in obtaining counsel and presenting their cases. Those returned to Mexican border cities were subject to severe security risks. The program continued to impose significant monetary and diplomatic costs on the United States to maintain it, and there was no evidence the reinstated program had any impact on border crossings. Despite assurances by the Biden administration that MPP 2.0 would be better than the first program, the program once again failed to “protect” migrants.